by Robyn Bolton | Oct 6, 2019 | Tips, Tricks, & Tools

On August 27, Pumpkin Spice season began. It was the earliest ever launch of Starbucks’ Pumpkin Spice Latte and it kicked off a season in which everything from Cheerios to protein powder to dog shampoo promises the nostalgia of Grandma’s pumpkin pie.

Since its introduction in 2003, the Pumpkin Spice Latte has attracted its share of lovers and haters but, because it’s a seasonal offering, the hype fades almost as soon as it appears.

Sadly, the same cannot be said for its counterpart in corporate innovation — The Shark Tank/Hackathon/Lab Week.

It may seem unfair to declare Shark Tanks the Pumpkin Spice of corporate innovation, but consider the following:

- They are events. There’s nothing wrong with seasonal flavors and events. After all, they create a sense of scarcity that spurs people to action and drives companies’ revenues. However, there IS a great deal wrong with believing that innovation is an event. Real innovation is not an event. It is a way of thinking and problem-solving, a habit of asking questions and seeking to do things better, and of doing the hard and unglamorous work of creating, learning, iterating, and testing required to bring innovation — something different that creates value — to life.

- They appeal to our sense of nostalgia and connection. The smell and taste of Pumpkin Spice bring us back to simpler times, holidays with family, pie fresh and hot from the oven. Shark Tanks do the same. They remind us of the days when we believed that we could change the world (or at least fix our employers) and when we collaborated instead of competed. We feel warm fuzzies as we consume (or participate in) them, but the feelings are fleeting, and we return quickly to the real world.

- They pretend to be something they’re not. Starbucks’ original Pumpkin Spice Latte was flavored by cinnamon, nutmeg, and clove. There was no pumpkin in the Pumpkin Spice. Similarly, Shark Tanks are innovation theater — events that give people an outlet for their ideas and an opportunity to feel innovation-y for a period of time before returning to their day-to-day work. The value that is created is a temporary blip, not lasting change that delivers real business value.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

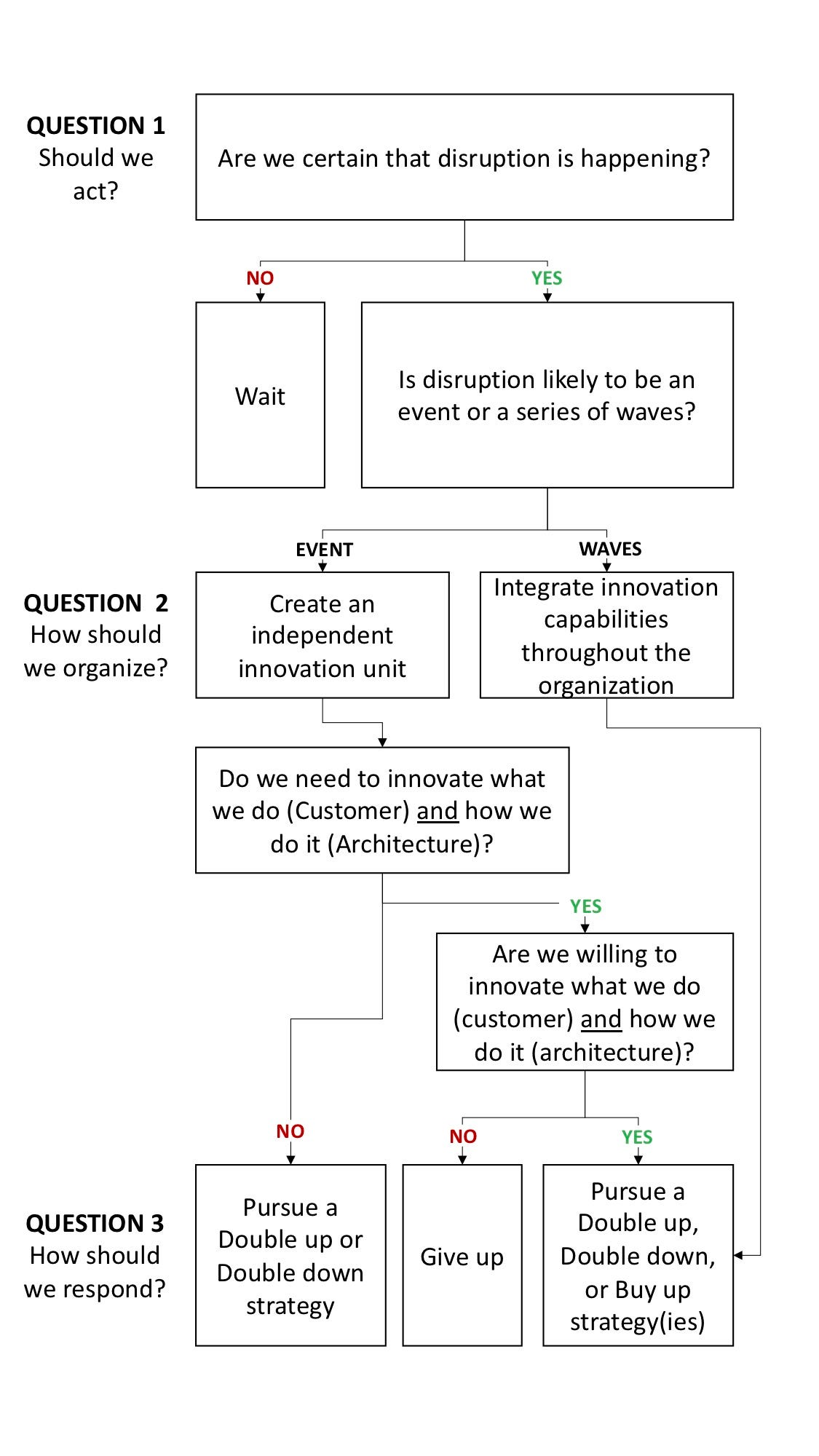

If you’re serious about walking the innovation talk, Shark Tanks can be a great way to initiate and accelerate building a culture and practice of innovation. But they must be developed and deployed in a thoughtful way that is consistent with your organization’s strategy and priorities.

- Make Shark Tanks the START of an innovation effort, not a standalone event. Clearly establish the problems or organizational priorities you want participants to solve and the on-going investment (including dedicated time) that the company will make in the winners. Allocate an Executive Sponsor who meets with the team monthly and distribute quarterly updates to the company to share winners’ progress and learnings

- Act with courage and commitment. Go beyond the innovation warm fuzzies and encourage people to push the boundaries of “what we usually do.” Reward and highlight participants that make courageous (i.e. risky) recommendations. Pursue ideas that feel a little uncomfortable because the best way to do something new that creates value (i.e. innovate) is to actually DO something NEW.

- Develop a portfolio of innovation structures: Just as most companies use a portfolio of tools to grow their core businesses, they need a portfolio of tools to create new businesses. Use Shark Tanks to the surface and develop core or adjacent innovation AND establish incubators and accelerators to create and test radical innovations and business models AND fund a corporate VC to scout for new technologies and start-ups that can provide instant access to new markets.

In closing…

Whether you love or hate Pumpkin Spice Lattes you can’t deny their impact. They are, after all, Starbucks’ highest-selling seasonal offering. But it’s hard to deny that they are increasingly the subject of mocking memes and eye-rolls, a sign that their days, and value, maybe limited.

(Most) innovation events, like Pumpkin Spice, have a temporary effect. But not on the bottom-line. During these events, morale, and team energy spike. But, as the excitement fades and people realize that nothing happened once the event was over, innovation becomes a meaningless buzzword, evoking eye rolls and Dilbert cartoons.

Avoid this fate by making Shark Tanks a lasting part of your innovation menu — a portfolio of tools and structures that build and sustain a culture and practice of innovation, one that creates real financial and organizational value.

by Robyn Bolton | Jun 9, 2019 | Innovation

“What do you plan to do on vacation?” my friend asked.

“Nothing…”

Long silence

“…And it will be amazing.”

We live in a world that confuses activity with achievement so I should not have been surprised that the idea of deliberately doing nothing stunned my friend into silence.

After all, when people say, “I wish I had nothing to do” they usually mean “I wish I could choose what I do with my time.” And, when they do have the opportunity to choose, very few choose to do nothing.

Why does the idea of doing nothing make us so uncomfortable?

To put it bluntly, busy-ness is a status symbol.

In their paper, “Conspicuous Consumption of Time: When Busyness and Lack of Leisure Time Become a Status Symbol,” professors Silvia Bellezza (Columbia Business School), Neeru Paharia (Georgetown University), and Anat Keinan (Harvard University), wrote that people’s desire to be perceived as time-starved is

“driven by the perceptions that a busy person possesses desired human capital characteristics (competence, ambition) and is scarce and in demand on the job market.”

We didn’t always believe this.

For most of human history, we’ve had a pretty balanced view of the need for both work and leisure. Aristotle argued that virtue was obtainable through contemplation, not through endless activity. Most major religions call for a day of rest and reflection. Even 19th-century moral debates, as recorded by historian EO Thompson, recognized the value of hard work AND the importance of rest.

So what happened?

While it’s easy to say that we have to work more because of the demands of our jobs, the data says otherwise. In fact, according to a working paper by Jonathan Gershuny, a time-expert based on the UK, actual time spent at work has not increased since the 1960s.

The actual reason may be that we want to work more. According to economist Robert Frank, those who identify as workaholics believe that:

“building wealth…is a creative process, and the closest thing they have to fun.”

We choose to spend time working because Work — “the job itself, the psychic benefits of accumulating money, the pursuit of status, and the ability to afford the many expensive enrichments of an upper-class lifestyle” according to an article in The Atlantic — is what we find most fulfilling.

It’s not that I like working, I just don’t like wasting time.

We tend to equate doing nothing with laziness, apathy, a poor work ethic, and a host of other personality flaws and social ills. But what if that’s not true.

What if, in the process of doing nothing, we are as productive as when we do something?

Science is increasingly showing this to be the case.

Multiple fMRI studies have revealed the existence of the default mode network (DMN), a large-scale brain network that is most active when we’re day-dreaming. Researchers at the University of Southern California argue that

“downtime is, in fact, essential to mental processes that affirm our identities, develop our understanding of human behavior and instill an internal code of ethics — processes that depend on the DMN.”

The results of harnessing the power of your DMN are immense:

More creativity. The research discussed in Scientific American suggests that DMN is more active in creative people. For example, according to Psychology Today:

- The most recorded song of all time, “Yesterday” by The Beatles, was ‘heard’ by Paul McCartney as he was waking up one morning. The melody was fully formed in his mind, and he went straight to the piano in his bedroom to find the chords to go with it, and later found words to fit the melody.

- Mozart described how his musical ideas ‘flow best and most abundantly.’ when he was alone ‘traveling in a carriage or walking after a good meal, or during the night when I cannot sleep… Whence and how they come, I know not, nor can I force them.’

- Tchaikovsky described how the idea for a composition usually came ‘suddenly and unexpectedly… It takes root with extraordinary force and rapidity, shoots up through the earth, puts forth branches and leaves, and finally blossoms.’

More productivity. According to an essay in The New York Times, “Idleness is not just a vacation, an indulgence or a vice; it is as indispensable to the brain as vitamin D is to the body, and deprived of it we suffer a mental affliction as disfiguring as rickets. The space and quiet that idleness provides is a necessary condition for standing back from life and seeing it whole, for making unexpected connections and waiting for the wild summer lightning strikes of inspiration — it is, paradoxically, necessary to getting any work done.”

Less burnout. Regardless of how many hours you work, consider this: researchers have found that it takes 25 minutes to recover from a phone call or an e-mail. On average, we are interrupted every 11 minutes which means that we can never catch up, we’re always behind.

That feeling of always being behind leads to burn-out which the World Health Organization officially recognized as a medical condition defined as a “syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” and manifests with the following symptoms:

- Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion

- Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job

- Reduced professional efficacy

Doing nothing, quieting our minds and not focusing on any particular task, can actually help reset our bodies systems, quieting the release of stress chemicals, slowing our heart rates, and improving our mental and physical energy

Better health. Multiple studies indicate that idleness “produces many health benefits including, but not limited to, reduced heart rate, better digestion, improvements in mood, and a boost in overall emotional well-being — which, of course, affects everything on a biochemical and physiological level, thereby serving as a major deciding factor on whether or not we fall ill, and/or remain ill. Mental downtime also replenishes glucose and oxygen levels in the brain, and allows our brains to process and file things, which leaves us feeling more rested and clear-headed, promotes a stronger sense of self-confidence, and…more willing to we trust change.”

Fine, you convinced me. How can I do nothing?

There are the usual suspects — vacations, meditation, and physical exercise — but, if you’re anything like me, the thought of even finding 5 minutes to listen to a meditation app is so overwhelming that I never even start.

An easier place to start, in my experience, is in intentionally working nothing into the moments that are already “free.” Here are three of my favorite ways to work a bit of nothing into my day.

Make the Snooze button work for you. When my alarm goes off, I instinctively hit the Snooze button because, I claim, it is my first and possibly only victory of the day. It’s also a great way to get 9 minutes of thoughtful quiet nothingness in which I can take a few deep breaths, scan my body for any aches and pains, and make sure that I’m calm and my mind is quiet when I get out of bed.

Stare out the window. I always place my computer next to a window so that I can stare out the window for a few minutes throughout the day and people think I’m thinking deep thoughts. Which I am. Subconsciously. Lest anyone accuse me of being lazy or unproductive while I watch the clouds roll by, I simply point them to research that shows “that individuals who took five to ten minute breaks from work to do nothing a few times a day displayed an approximately 50% increase in their ability to think clearly and creatively, thus rendering their work far more productive.

Bring the beach to you. Research from a variety of places, from the UK Census to The Journal of Coastal Zone Management, indicate that our brains and bodies benefit from time at the beach. But, if you can’t go to the beach, there are lots of ways to bring the beach to you. Perhaps the simplest is to bring more blue into your environment. Most people associate blue with feelings of calm and peace and a study published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science found that the color blue can boost creativity. Even putting a picture of a beach (or your own personal happy place) on your desk or computer screen can trigger your brain to slow down, relax, and possibly trigger your DMN.

With so many benefits, isn’t it time you started doing more nothing?

by Robyn Bolton | Feb 21, 2019 | Tips, Tricks, & Tools

“I don’t know how I got into the program. I’m not innovative.”

For nearly two years, I’ve been the Dean of the Intrapreneurship Academy, a program I created in partnership with The Cable Center to help the industry’s rising stars learn how to be more effective innovators. Over the course of four cohorts, we’ve taught nearly 100 people from all over the world (US, India, Honduras, Panama, Columbia…just to name a few) the tools and mindsets of successful intrapreneurs and supported them as they did the hard work of making innovation happen in their companies.

And in every single cohort, a significant number of people pull me aside and say, “I don’t know how I got into the program. I’m not innovative.”

To which I respond, “The fact that you don’t think you are an innovator but someone in your company does means that you are.”

Why is this? Why do so many people have a misperception about whether or not they’re innovative? Why do people see others as innovative even if they don’t see themselves that way? While we’re on the subject, what makes someone an “innovator” to begin with?

What is an Innovator?

According to Dictionary.com an Innovator is “a person who introduces new methods, ideas, or products.”

That’s a perfectly good definition but it also means that when my husband says, “I have an idea, let’s install new lighting in my home office,” that he is an innovator and I’m just not willing to concede that (plus he usually chooses to sit in the dark so I’m not sure why he needs new lighting).

A better definition is rooted in my preferred definition of “innovation” and would be something like, “A person who does something new or different that creates value.” The last two words in that definition are critical because they differentiate invention (something new or different) from innovation (something new and different that create value) and therefore inventors from innovators. And, since I’m not convinced that new lighting will create value, gets me out of having to agree with my husband’s claim that his idea was innovative.

How NOT to spot an Innovator

Before we get into how to spot an innovator, I think it’s important to dispel a few myths that often lead to people being misidentified as innovators.

- They have a “look.” For a period of time in the early aughts, if you wore a black turtleneck you were likely to be labeled an “innovator” and, as a result, have everyone stare at you with eager anticipation of your next brilliant world-changing idea. Then the magic uniform became a hoodie and flip-flops, or thick-black rimmed hipster glasses ideally paired with a flannel shirt and ankle-length jeans. Hate to break it to you but, unless you live in the Marvel Universe, clothes do not imbue in their wearers with special super-powers, so don’t assume that someone is innovative just because they’re wearing the outfit du jour.

- They use innovation words all the time. Just because you can say a word doesn’t mean you know what it means, let alone that you can act on it. I can say “Python” and “Pandas” and “Numpy” (pronounced num-pie) and maybe even use those words in a sentence but I can’t define them for you and I sure as heck can write a program in Python or explain how and why pandas and numpies would be useful in such a program (my husband can, it’s what he does in his home office with the supposedly poor lighting). So if someone is always using terms like “disrupt” or “business model” or “lean start-up” or “design thinking,” ask them to define those terms AND explain how to put them in practice. If they can’t accurately do that, they’re not true innovators.

- They tell you that they’re innovative. One of my favorite quotes is by Margaret Thatcher who said, “Being in power is like being a lady…if you have to tell people you are, you aren’t.” The same thing is true for Innovators. If someone goes around telling people that they’re an innovator or that they’re an “ideas person,” you can be confident that they are not.

How to Spot an Innovator

Now that we know how to spot pretenders, here’s how to spot the real thing:

- They ask questions AND they listen to the answers. Lots of people ask questions but Innovators ask questions rooted in curiosity and a selfless desire to make things better. They say things like, “Why are we doing it this way?” and “What if we tried it that way?” and “I know we’ve always done it this way but what if…?” When you give them an answer, they listen and incorporate the new information into their thinking and their ideas.

- They’re not afraid to try doing things differently. Maintaining the status quo is safe and no one ever got fired for following the rules. But playing safe and following the rules doesn’t move us forward, it keeps us where we are (and maybe even causes us to fall behind). But doing something different involves taking a risk and that can be scary. Innovators are willing to take on that risk because helping others by improving or creating things is more important to them than their own comfort.

- They’re more interested in Doing than Talking. Let’s be honest, it’s fun to talk about innovation. It’s energizing to be part of a brainstorming session with brightly colored sticky notes flying around. It’s exciting to get together a small team to come up with an idea and pitch that idea to a Shark Tank. It’s fun to go on field trips to incubators and accelerators. But innovators don’t stop there, they don’t view those activities as signs of innovation success. They push to prototype and test the best idea from the brainstorming session, they demand dedicated funding and resources to bring their Shark Tank winning idea to life, and they do the hard slow work of applying their field trip lessons to foster a culture of innovation within the organization.

The innovators I teach and work with do all of the 3 things listed above and doing those things come so naturally to them that they don’t realize how uncommon, difficult, and important doing these things is. And yes, some of them also wear black turtlenecks or hoodies or hipster glasses (or all three at the same time!) but they don’t do wear these things because they’re innovators. They wear these things because they’re comfortable. And comfort is of the utmost importance when you’re doing the hard work of innovation.