by Robyn Bolton | Dec 16, 2025 | Just for Fun, Leadership, Tips, Tricks, & Tools, Uncategorized

Everybody loves a Top X list. This past week I’ve read the Top 100 Best Comedy Movies of All Time, The 100 Best Episodes of the Century, and the NYT’s 100 Notable Books of 2025. And all this before we’re inundated with the Top 10 lists sports, politics, celebrity news, world news, and whatever other topic a writer can dream up.

Top X Lists are about big things, events that affect everyone or that will be remembered for decades. And while those Macro-moments are what stand out in our memories, they rarely define our everyday existence.

What are Micro-moments?

I first heard of Micro-moments in an interview between Dan Shipper, founder of Every, and Henrik Werdelin, founder of Prehype (and incubator that helped launch Barkbox and Ro Health). According to Werdelin:

Micro-moments for me are things when I’m in flow and things where I’m happy. It can’t be a big thing like having a family. It has to be a very concrete things like I like walking over the Brooklyn Bridge in the morning. It’s just something I get profoundly happy about, right? Or I like being in brainstorm meetings with (other entrepreneurs)

But his list of Micro-moments isn’t just a new-age happiness manifestation, it’s an actual decision-making tool. Werdelin explains:

I was basically trying to figure out what to do next and I was keeping all my options open. I got offered a job to run BBC Digital on the international side and then I got offered a job at a design agency called Wolf Collins who had an incredible CEO.

And so, I ended up having these 30 concrete [moments] where I’ve done stuff and then I started to use that as a way to measure options that would be thrown at me. The BBC sounded like it would be a lot of money, and it was like a cool job, and it would give me, I guess, self-esteem for a second. But then when I looked at what it would entail, none of the Micro-moments would be included so I was like, “ah, probably not for me.”

My first Micro-reactions

- Eye roll: Thank goodness you had a list of Micro-moments so you could avoid the soul sucking horror of running BBC Digital!

- Righteous indignation: Do you have any idea how hard it is out there to find a job? People would be thrilled to have a job that delivers only ONE Micro-moment of happiness?!

- Breathe: What a second. What if Mico-moments don’t determine your role. What if Micro-moments…perhaps…mean a little bit more! (yes, that is a terrible rephrasing of the Grinch’s epiphany)

Micro-moments are more than moments of flow and joy. They’re the moments that make up our lives, relationships, and view of the world. They’re the moments that should be on our Top 10 lists but too often get crowded out by noisier, bigger moments.

They’re also things we can create, design for, and sometimes even control.

What are YOUR Micro-moments?

As the period of end-of-year reflection approaches, think about your Micro-moments. What small, concrete moments that brought you flow, joy, or peace, this year? Where were you? What were you doing? Who were you with? Jot them down

When the new year dawns, go back to your list and get curious. What are the common themes, people, places, and activities in your Micro-moments. Write down what you notice.

As the year kicks into gear and everyone settles back into work and school routines, return to your list and start planning. How might you create more Micro-moments?

Life is made up of moments. Many of them are beyond our control. But some of them aren’t. And wouldn’t it be great to know which ones make us happiest so we can experience them more often?

by Robyn Bolton | Oct 6, 2025 | 5 Questions, Customer Centricity, Innovation, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

For decades, we’ve faithfully followed innovation’s best practices. The brainstorming workshops, the customer interviews, and the validated frameworks that make innovation feel systematic and professional. Design thinking sessions, check. Lean startup methodology, check. It’s deeply satisfying, like solving a puzzle where all the pieces fit perfectly.

Problem is, we’re solving the wrong puzzle.

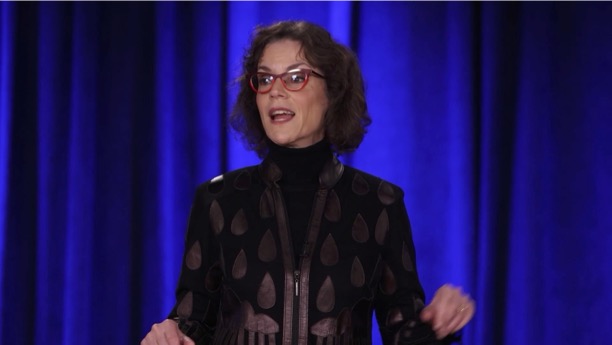

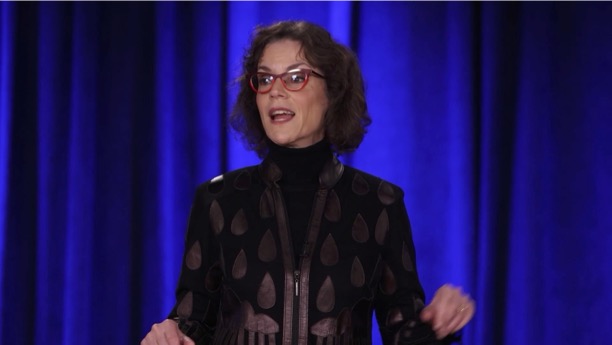

As Ellen Di Resta points out in this conversation, all the frameworks we worship, from brainstorming through business model mapping, are business-building tools, not idea creation tools.

Read on to learn why our failure to act on the fundamental distinction between value creation and value capture causes too many disciplined, process-following teams to create beautiful prototypes for products nobody wants.

Robyn: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about innovation that organizations need to unlearn?

Ellen: That the innovation best practices everyone’s obsessed with work for the early stages of innovation.

The early part of the innovation process is all about creating value for the customer. What are their needs? Why are their Jobs to be Done unsatisfied? But very quickly we shift to coming up with an idea, prototyping it, and creating a business plan. We shift to creating value for the business, before we assess whether or not we’ve successfully created value for the customer.

Think about all those innovation best practices. We’ve got business model canvas. That’s about how you create value for the business. Right? We’ve got the incubators, accelerators, lean, lean startup. It’s about creating the startup, which is a business, right? These tools are about creating value for the business, not the customer.

R: You know that Jobs to be Done is a hill I will die on, so I am firmly in the camp that if it doesn’t create value for the customer, it can’t create value for the business. So why do people rush through the process of creating ideas that create customer value?

E: We don’t really teach people how to develop ideas because our culture only values what’s tangible. But an idea is not a tangible thing so it’s hard for people to get their minds around it. What does it mean to work on it? What does it mean to develop it? We need to learn what motivates people’s decision-making.

Prototypes and solutions are much easier to sell to people because you have something tangible that you can show to them, explain, and answer questions about. Then they either say yes or no, and you immediately know if you succeeded or failed.

R: Sounds like it all comes down to how quickly and accurately can I measure outcomes?

E: Exactly. But here’s the rub, they don’t even know they’re rushing because traditional innovation tools give them a sense of progress, even if the progress is wrong.

We’ve all been to a brainstorm session, right? Somebody calls the brainstorm session. Everybody goes. They say any idea is good. Nothing is bad. Come up with wild, crazy ideas. They plaster the walls with 300 ideas, and then everybody leaves, and they feel good and happy and creative, and the poor person who called the brainstorm is stuck.

Now what do they do? They look at these 300 ideas, and they sort them based on things they can measure like how long it’ll take to do or how much money it’ll cost to do it. What happens? They end up choosing the things that we already know how to do! So why have the brainstorm?”

R: This creates a real tension: leadership wants progress they can track, but the early work is inherently unmeasurable. How do you navigate that organizational reality?

E: Those tangible metrics are all about reliability. They make sure you’re doing things right. That you’re doing it the same way every time? And that’s appropriate when you know what you’re doing, know you’re creating value for the customer, and now you’re working to create value for the business. Usually at scale

But the other side of it? That’s where you’re creating new value and you are trying to figure things out. You need validity metrics. Are we doing the right things? How will we know that we’re doing the right things.

R: What’s the most important insight leaders need to understand about early-stage innovation?

E: The one thing that the leader must do is run cover. Their job is to protect the team who’s doing the actual idea development work because that work is fuzzy and doesn’t look like it’s getting anywhere until Ta-Da, it’s done!

They need to strategically communicate and make sure that the leadership hears what they need to hear, so that they know everything is in control, right? And so they’re running cover is the best way to describe it. And if you don’t have that person, it’s really hard to do the idea development work.”

But to do all of that, the leader also must really care about that problem and about understanding the customer.

We must create value for the customer before we can create value for the business. Ellen’s insight that most innovation best practices focus on the latter is devastating. It’s also essential for all the leaders and teams who need results from their innovation investments.

Before your next innovation project touches a single framework, ask yourself Ellen’s fundamental question: “Are we at a stage where we’re creating value for the customer, or the business?” If you can’t answer that clearly, put down the canvas and start having deeper conversations with the people whose problems you think you’re solving.

To learn more about Ellen’s work, check out Pearl Partners.

To dive deeper into Ellen’s though leadership, visit her Substack – Idea Builders Guild.

To break the cycle of using the wrong idea tools, sign-up for her free one-hour workshop.

by Robyn Bolton | Sep 30, 2025 | Leading Through Uncertainty, Strategy, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

Just as we got used to VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) futurists now claim “the world is BANI now.” BANI (brittle, anxious, nonlinear, incomprehensible) is much worse than VUCA and reflects “the fractured, unpredictable state of the modern world.”

Not to get too Gen X on the futurists who coined and are spreading this term but…shut up.

Is the world fractured and unpredictable? Yes.

Does it feel brittle? Are we more anxious than ever? Are things changing at exponential speed, requiring nonlinear responses? Does the world feel incomprehensible? Yes, to all.

Naming a problem is the first step in solving it. The second step is falling in love with the problem so that we become laser focused on solving it. BANI does the first but fails at the second. It wallows in the problem without proposing a path forward. And as the sign says, “Ain’t nobody got time for this.”

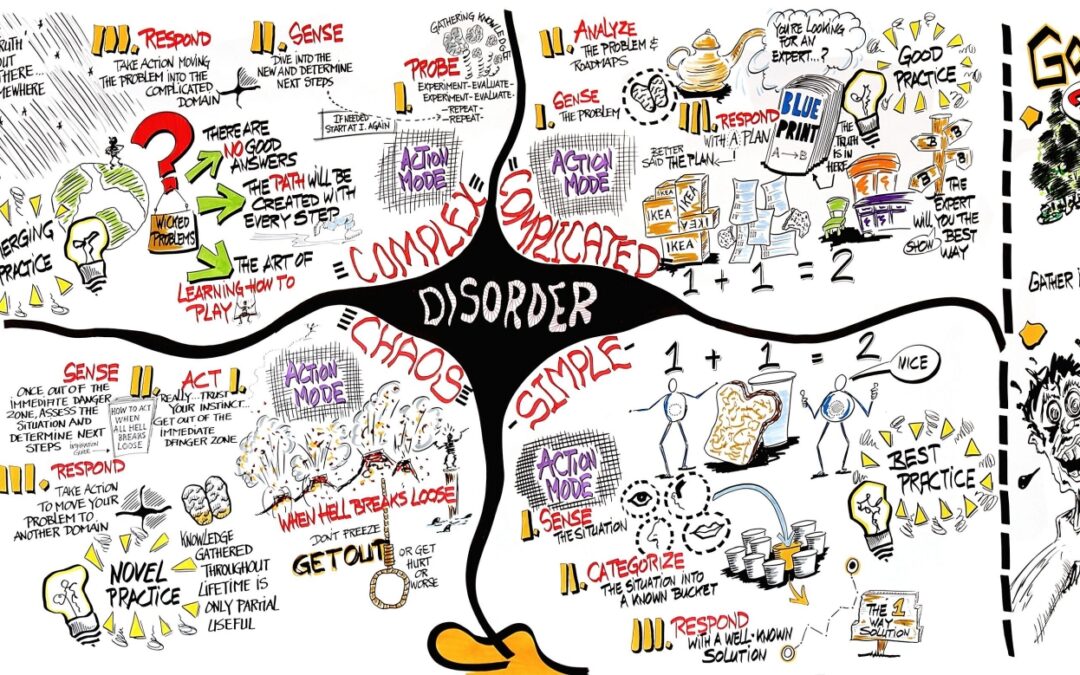

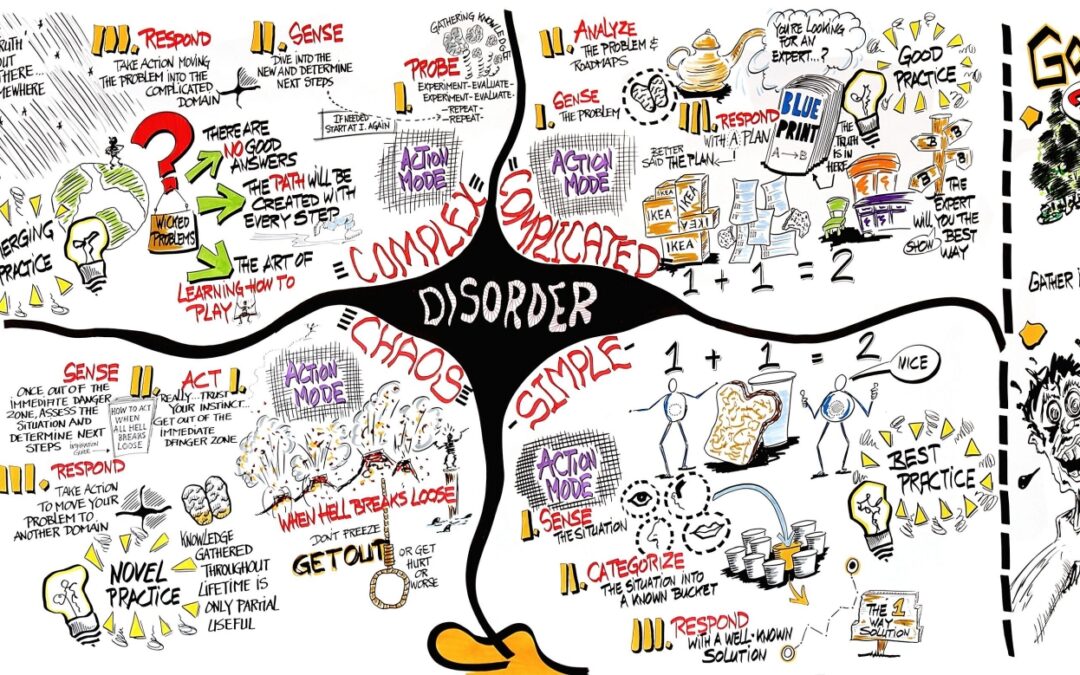

(Re)Introducing the Cynefin Framework

The Cynefin framework recognizes that leadership and problem-solving must be contextual to be effective. Using the Welsh word for “habitat,” the framework is a tool to understand and name the context of a situation and identify the approaches best suited for managing or solving the situation.

It’s grounded in the idea that every context – situation, challenge, problem, opportunity – exists somewhere on a spectrum between Ordered and Unordered. At the Ordered end of the spectrum, cause and affect are obvious and immediate and the path forward is based on objective, immutable facts. Unordered contexts, however, have no obvious or immediate relationship between cause and effect and moving forward requires people to recognize patterns as they emerge.

Both VUCA and BANI point out the obvious – we’re spending more time on the Unordered end of the spectrum than ever. Unlike the acronyms, Cynefin helps leaders decide and act.

5 Contexts. 5 Ways Forward

The Cynefin framework identifies five contexts, each with its own best practices for making decisions and progress.

On the Ordered end of the spectrum:

- Simple contexts are characterized by stability and obvious and undisputed right answers. Here, patterns repeat, and events are consistent. This is where leaders rely on best practices to inform decisions and delegation, and direct communication to move their teams forward.

- Complicated contexts have many possible right answers and the relationship between cause and effect isn’t known but can be discovered. Here, leaders need to rely on diverse expertise and be particularly attuned to conflicting advice and novel ideas to avoid making decisions based on outdated experience.

On the Unordered end of the spectrum:

- Complex contexts are filled with unknown unknowns, many competing ideas, and unpredictable cause and effects. The most effective leadership approach in this context is one that is deeply uncomfortable for most leaders but familiar to innovators – letting patterns emerge. Using small-scale experiments and high levels of collaboration, diversity, and dissent, leaders can accelerate pattern-recognition and place smart bets.

- Chaos are contexts fraught with tension. There are no right answers or clear cause and effect. There are too many decisions to make and not enough time. Here, leaders often freeze or make big bold decisions. Neither is wise. Instead, leaders need to think like emergency responders and rapidly response to re-establish order where possible to bring the situation into a Complex state, rather than trying to solve everything at once.

The final context is Disorder. Here leaders argue, multiple perspectives fight for dominance, and the organization is divided into fractions. Resolution requires breaking the context down into smaller parts that fit one of the four previous contexts and addressing them accordingly.

The Only Way Out is Through

Our VUCA/BANI world isn’t going to get any simpler or easier. And fighting it, freezing, or fleeing isn’t going to solve anything. Organizations need leaders with the courage to move forward and the wisdom and flexibility to do so in a way that is contextually appropriate. Cynefin is their map.

by Robyn Bolton | Sep 23, 2025 | Innovation, Metrics, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

It’s time for your company’s All-Hands meeting. Your CEO stands on stage and announces ambitious innovation goals, talking passionately about the importance of long-term thinking and breakthrough results. Everyone nods enthusiastically, applauds politely, and returns to their desks to focus on hitting this quarter’s numbers. After all, that’s what their bonuses depend on.

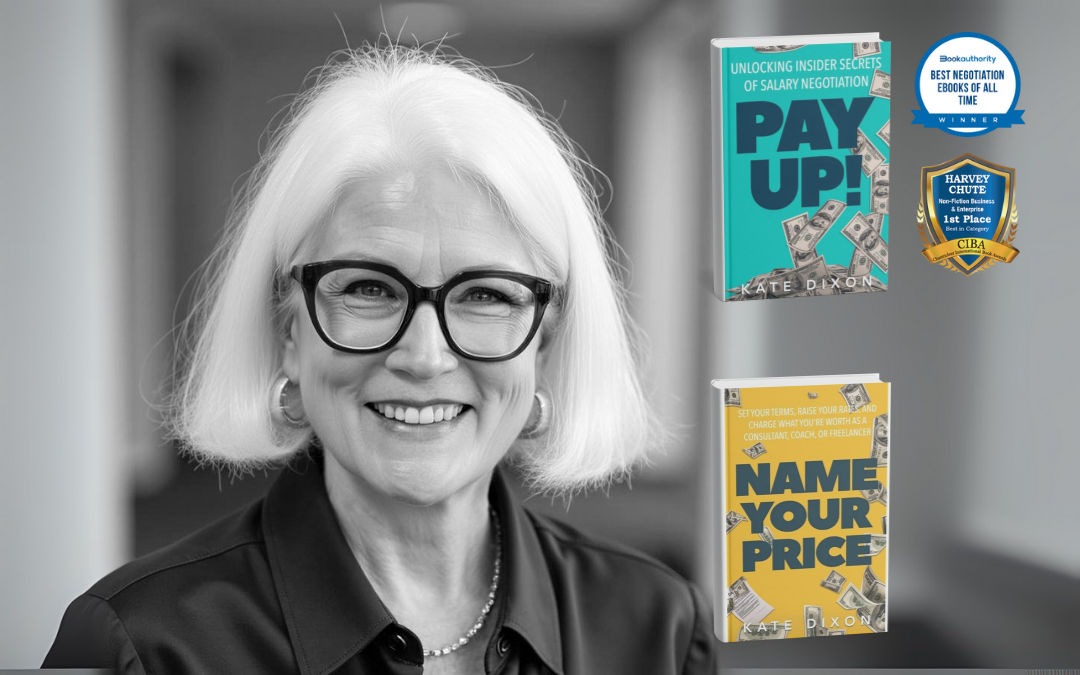

Kate Dixon, compensation expert and founder of Dixon Consulting, has watched this contradiction play out across Fortune 500 companies, B Corps, and startups. Her insight cuts to the heart of why so many innovation initiatives fail: we’re asking people to think long-term while paying them to deliver short-term.

In our conversation, Kate revealed why most companies are inadvertently sabotaging their own innovation efforts through their compensation structures—and what the smartest organizations are doing differently.

Robyn Bolton: Kate, when I first heard you say, “compensation is the expression of a company’s culture,” it blew my mind. What do you mean by that?

Kate Dixon: If you want to understand what an organization values, look at how they pay their people: Who gets paid more? Who gets paid less? Who gets bigger bonuses? Who moves up in the organization and who doesn’t? Who gets long-term incentives?

The answers to these questions, and a million others, express the culture of the organization. How we reward people’s performance, either directly or indirectly, establishes and reinforces cultural norms. Compensation is usually the biggest, if not the biggest, expenses that a company has so they’re very thoughtful and deliberate about how it is used. Which is why it tells you what the company actually does value.

RB: What’s the biggest mistake companies make when trying to incentivize innovation?

KD: Let’s start by what companies are good at when it comes to compensations and incentives. They’re really good about base pay, because that’s the biggest part of pay for most people in an organization. Then they spend the next amount of time and effort trying to figure out the annual bonus structure. After that comes other benefits, like long term incentives, assuming they don’t fall by the wayside.

As you know, innovation can take a long time to payout, so long-term incentives are key to encouraging that kind of investment. Stock options and restricted shares are probably the most common long-term incentives but cash bonuses, phantom stock, and ESOP shares in employee-owned companies are also considered long term incentives.

Large companies are pretty good using some equity as an incentive, but they tie it t long term revenue goals, not innovation. As you often remind us, “innovation is a means to the end, which is growth,” so tying incentives to growth isn’t bad but I believe that we can do better. Tying incentives to the growth goals and how they’re achieved will go a long way towards driving innovation.

RB: I’ve worked in and with big companies and I’ve noticed that while they say, “innovation is everyone’s job,” the people who get long-term incentives are typically senior execs. What gives?

Long-term incentives are definitely underutilized, below the executive level, and maybe below the director level. Assuming that most companies’ innovation efforts aren’t moonshots that take decades to realize, it makes a ton of sense to use long-term incentives throughout the organization and its ecosystem. However, when this idea is proposed, people often pushback because “it’s too complex” for folks lower in the organization, “they wouldn’t understand.” or “they won’t appreciate it”. That stance is both arrogant and untrue. I’ve consistently seen that when you explain long-term incentives to people, they do get it, it does motivate them, and the company does see results.

RB: Are there any examples of organizations that are getting this right?

We’re seeing a lot more innovative and interesting risk-taking behaviors in companies that are not primarily focused on profit.

Our B Corp clients are doing some crazy, cool stuff. We have an employee-owned company that is a consulting firm, but they had an idea for a software product. They launched it and now it’s becoming a bigger and bigger part of their business.

Family-owned or public companies that have a single giganto shareholder are also hotbeds of long-term thinking and, therefore, innovation. They don’t have that same quarter to quarter pressure that drives a relentless focus on what’s happening right now and allows people to focus on the future.

What’s the most important thing leaders need to understand about compensation and innovation?

If you’re serious about innovation, you should be incentivizing people all over the organization. If you want innovation to be a more regular piece of the culture so you get better results, you’ve got to look at long term incentives. Yes, you should reward people for revenue and short-term goals. But you also need to consider what else is a precursor to our innovation. What else is makes the conditions for innovating better for people, and reward that, too.

Kate’s insight reveals the fundamental contradiction at the heart of most companies’ innovation struggles: you can’t build long-term value with short-term thinking, especially when your compensation system rewards only the latter.

What does your company’s approach to compensation say about its culture and values?

by Robyn Bolton | Sep 16, 2025 | Leading Through Uncertainty, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

When a project is stuck and your team is trying to manage uncertainty, what do you hear most often:

- “We’re so afraid of making the wrong decision that we don’t make any decisions.”

- “We don’t have time to explore a bunch of stuff. We need to make decisions and go.”

- “The problem is so multi-faceted, and everything affects everything else that we don’t know where to start.”

I’ve heard all three this week, each spoken by teams leads who cared deeply about their projects and teams.

Differentiating between risk and uncertainty and accepting that uncertainty would never go away, just change focus helped relieve their overwhelm and self-doubt.

But without a way to resolve the fear, time-pressure, and complexity, the project would stay stuck with little change of progressing to success.

Turn uncertainty into an asset

It’s a truism in the field of innovation that you must fall in love with the problem, not the solution. Falling in love with the problem ensures that you remain focused on creating value and agnostic about the solution.

While this sounds great and logically makes sense, most struggle to do it. As a result, it takes incredible strength and leadership to wrestle with the problem long enough to find a solution.

Uncertainty requires the same strength and leadership because the only way out of it is through it. And, research shows, the process of getting through it, turns it into an asset.

3 Steps to turn uncertainty into an asset

Research in the music and pharmaceutical industries reveals that teams that embraced uncertainty engaged in three specific practices:

- Embrace It: Start by acknowledging the uncertainty and that things will change, go wrong, and maybe even fail. Then stay open to surprise and unpredictability, delving into the unknown “by being playful, explorative, and purposefully engaging in ventures with indeterminate outcome.”

- Fix It: Especially when dealing with Unknowable Uncertainty, which occurs when more info supports several different meanings rather than pointing to one conclusion, teams that succeed make provisional decisions to “fix” an uncertain dimension so they can move forward while also documenting the rationale for the fix, setting a date to revisit it, and criteria for changing it.

- Ignore It: It’s impossible to embrace every uncertainty at once and unwise to fix too many uncertainties at the same time. As a result, some uncertainties, you just need to ignore. Successful teams adopt “strategic ignorance” “not primarily for purposes of avoiding responsibility [but to] allow postponing decisions until better ideas emerge during the collaborative process.

This practice is iterative, often leading to new knowledge, re-examined fixes, and fresh uncertainties. It sounds overwhelming but the teams that are explicit and intentional about what they’re embracing, fixing, and ignoring are not only more likely to be successful, but they also tend to move faster.

Put it into practice

Let’s return to NatureComp, a pharmaceutical company developing natural treatments for heart disease.

Throughout the drug development process, they oscillated between addressing What, Who, How, and Where Uncertainties. They did that by changing whether they embraced, fixed, or ignored each type of uncertainty at a given point:

![]()

As you can see, they embraced only one type of uncertainty to ensure focus and rapid progress. To avoid the fear of making mistakes, they fixed uncertainties throughout the process and returned to them as more information came available, either changing or reaffirming the fix. Ignoring uncertainties helped relieve feelings of being overwhelmed because the team had a plan and timeframe for when they would shift from ignoring to embracing or fixing.

Uncertainty is dynamic. You need to be dynamic, too.

You’ll never eliminate uncertainty. It’s too dynamic to every fully resolve. But by dynamically embracing, fixing, and ignore it in all its dimensions, you can accelerate your path to success.

by Robyn Bolton | May 21, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

“What will you do on vacation?” a colleague asked.

“Nothing,” I replied.

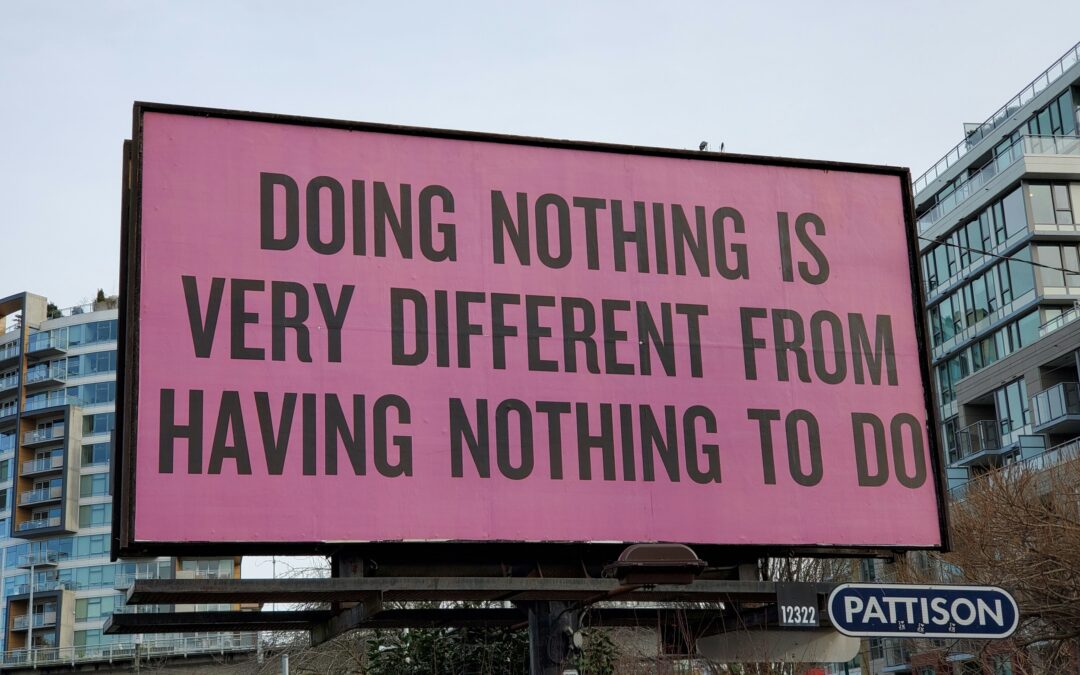

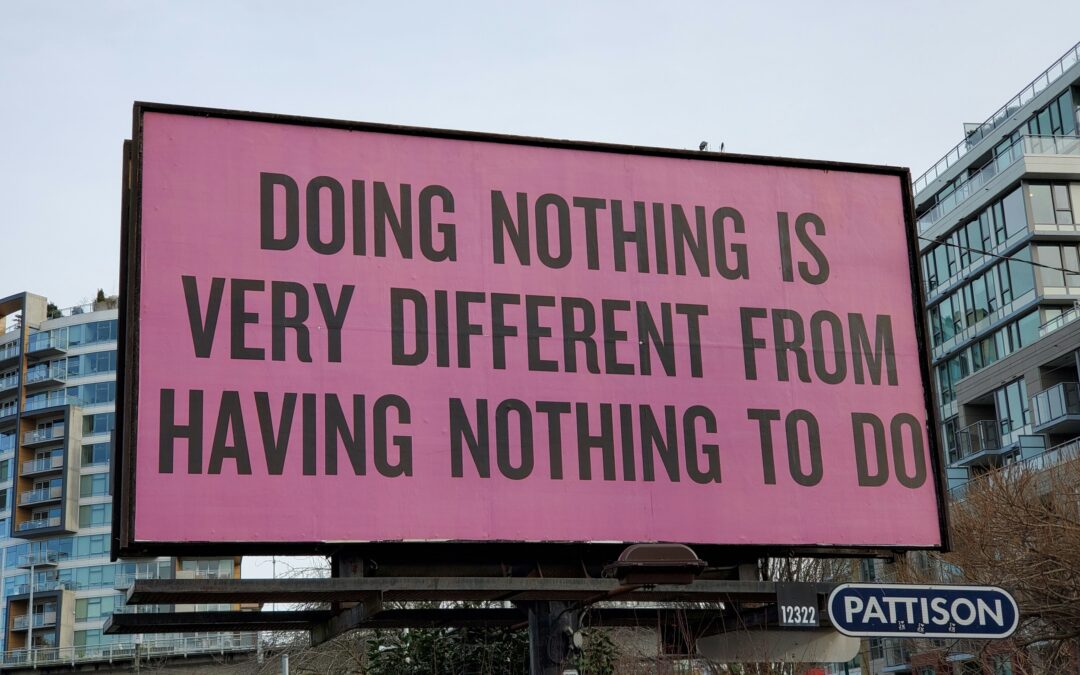

The uncomfortable silence that followed spoke volumes. In boardrooms and during quarterly reviews, we celebrate constant motion and back-to-back calendars. Yet, study after study shows that the most successful leaders embrace a counterintuitive edge: strategic idleness.

While your competitors exhaust themselves in perpetual busyness, research shows that deliberate mental downtime activates the brain networks responsible for strategic foresight, innovative solutions, and clear decision-making.

The Status Trap of Busy-ness

At one company I worked with, there was only one acceptable answer to “How are you doing?” “Busy.” The answer wasn’t a way to avoid an awkward hallway conversation. It was social currency. If you’re busy, you’re valuable. If you’re fine, you’re expendable.

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Consumer Research confirmed what Columbia, Georgetown, and Harvard researchers discovered: being busy is now a status symbol, signaling “competence, ambition, and scarcity in the market.”

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: your packed schedule is undermining the very outcomes you’re accountable for delivering.

Your Brain’s Innovation Engine

Neuroscience has confirmed what innovators have long practiced: Strategic Idleness. While you consciously “do nothing,” your default mode network (DMN) engages, making unexpected connections across stored information and experiences.

Recent research published in the journal Brain demonstrates that the DMN is activated during creative thinking, with a specific pattern of neural activity occurring during the search for novel ideas. This network is essential for both spontaneous thought and divergent thinking, core elements of innovation.

So if you’ve always wondered why you get your best ideas in the shower, it’s because your DMN is powered all the way up.

Three Ways to Power-Up Your Engine

Here are three executive-grade approaches to strategic idleness without more showers or productivity sacrifices:

- Pause for 10 Minutes Before Making a Decision

Before making high-stakes decisions, implement a mandatory 10-minute idleness period. No email, no conversation—just sitting. Research on cognitive recovery suggests that this brief reset activates your DMN, allowing for a more comprehensive consideration of variables and strategic implications.

- Take a Walking Meeting with Yourself

Block 20 minutes in your calendar each week for a solo walking meeting (and then take the walk!). No other attendees, no agenda, just walking. Researchers at Stanford University found that walking increases creative output by an average of 60% compared to sitting. The combination of physical movement and mental space creates ideal conditions for your brain to generate solutions to problems you didn’t know you had.

- Schedule 3-5 minutes of Strategic Silence before key discussions

Research on group dynamics shows that silent reflection before discussion can reduce groupthink and increase the quality of ideas by helping team members process information more deeply. Before you dive into a critical topic at your next leadership meeting, schedule 3-5 minutes of silence. Explain that this silence is for individual reflection and planning for the upcoming discussion, not for checking email or taking bathroom breaks. Acknowledge that it will feel awkward, but that it’s critical for the upcoming discussion and decision.

Remember, You’re Not Doing Nothing If You’re being Strategically Idle

The most valuable asset in your organization isn’t technology, capital, or even the products you sell. It’s the quality of thinking that goes into critical decisions. Strategic idleness isn’t inaction; it’s the deliberate cultivation of conditions that foster innovation, clear judgment, and strategic foresight.

While your competitors remain trapped in perpetual busyness, by using executive advantage of strategic idleness, your next breakthrough will present itself.

This is an updated version of the June 9, 2019, post, “Do More Nothing.”