by Robyn Bolton | Feb 8, 2026 | AI, Leadership, Leading Through Uncertainty, Strategic Foresight, Strategy

In 2023, Klarna’s CEO proudly announced it had replaced 700 customer service workers with AI and that the chatbot was handling two-thirds of customer queries. Labor costs dropped and victory was declared.

By 2025, Klarna was rehiring. Customer satisfaction had tanked. The CEO admitted they “went too far,” focusing on efficiency over quality.

Like Captain Robert Scott, Klarna misjudged the circumstance it was in, applied the wrong playbook, and lost. It thought it had facts but all it has was technical specs. It made tons of assumptions about chatbots’ ability to replace human judgment and how customers would respond.

Calibrated Decision Design, a process for diagnosing your circumstances before picking a playbook, consistently proves to be a quick and necessary step to ensure success.

When you have the facts and need results ASAP: Go NOW!

General Mills, like its competitors, had been digitizing its supply chain for years and so facts based on experience and a list of the facts it needed.

To close the gap and achieve end-to-end visibility in its supply chain, it worked with Palantir to develop a digital twin of its entire supply chain. Results: 30% waste reduction, $300 million in savings, decisions that took weeks now takes hours. It proves that you don’t need all the answers to make a move, but you need to know more than you don’t.

When you have hypotheses but can’t wait for results: Discovery Planning

Morgan Stanley Wealth Management’s (MSWM) clients expect advisors to bring them bespoke advice based on mountains of analysis, and insights. But it’s impossible for any advisor to process all that data. Confident that AI could help but uncertain whether its would improve relationships or create friction, MSWM partnered with OpenAI.

Within six months, they debuted a GenAI chatbot to help Financial Advisors quickly access the firm’s IP. Document retrieval jumped from 20% to 80% and 98% now use it daily. Two years later, MSWM expanded into a meeting summary tool to summarize meetings into actionable outputs and update the CRM with notes and follow-ups. A perfect example of how a series of experiments leads to a series of successes.

When you have facts and time to achieve results: Patient Planning

Drug discovery requires patience and, while the process may be predictable, the results aren’t. That’s why pharma companies need strategies that are thoughtfully planned as they are responsive.

Lilly is doing just that by investing in its own capabilities and building an ecosystem of partners. It started by launching TuneLab, a platform offering access to AI-enabled drug discovery models based on data that Lilly spent over $1 billion developing. A month later, the pharma giant announced a partnership with NVIDIA to build the pharmaceutical industry’s most powerful AI supercomputer. Two months later, it committed over $6 billion to a new manufacturing facility in Alabama. These aren’t billion-dollar bets, they’re thoughtful investments in a long-term future that allows Lilly to learn now and stay flexible as needs and technology evolve.

When you’re making assumptions and have time to learn: Resilient Strategy

There’s no way of knowing what the global energy system will look like in 40 years. That’s why Shell’s latest scenario planning efforts resulted in three distinct scenarios, Surge, Archipelagos, and Horizon. Multiple scenarios allows the company to “explore trade-offs between energy security, economic growth and addressing carbon emissions” and build resilient strategies to recognize which one is unfolding and pivot before competitors even spot what’s happening.

Stop benchmarking. Start diagnosing.

It’s easy to feel like you’re behind when it comes to AI. But the rush to act before you know the problem and the circumstances is far more likely to make you a cautionary tale than a poster child for success.

So, stop benchmarking what competitors do and start diagnosing the circumstances you’re in, so you use the playbook you need.

by Robyn Bolton | Feb 2, 2026 | AI, Leadership, Strategic Foresight, Strategy

It was a race. And the whole world was watching.

In 1911, Captain Robert Scott set out to reach the South Pole. He’d been to Antarctica before and because of his past success, he had more funding, more expertise, and more experience. He had all the equipment needed.

Racing him to fame, fortune and glory was Norwegian Roald Amundsen. Originally heading to the North Pole, he turned around when he learned that Robert Peary had beaten him there. He had dogs and skis, equipment perfect for the Arctic but unproven in Antarctica.

Amundsen won the race, by over a month.

Scott and his crew died 11 miles from the South Pole.

When the Playbook Stops Working

Scott wasn’t guessing. He’d tested motor sledges in the Alps. He’d seen ponies work on a previous Antarctic expedition. He built a plan around the best available equipment and the general playbook that had served British expeditions for decades: horses and motors move heavy loads, so use horses and motors.

It just wasn’t right for Antarctica. The motors broke down in the cold. The ponies sank through the ice. The plan that looked solid on paper fell apart the moment it met the actual environment it had to operate in.

The same thing is happening today with AI.

For decades, when new technologies emerge, executives have followed a similarly familiar playbook: assess the opportunity, build a business case, plan the rollout, execute.

And for decades it worked. Cloud migrations and ERP implementations were architectural changes to known processes with predictable outcomes. As time went on, information grew more solid, timelines became better understood, and the playbook solidified.

AI is different. Executives are so focused on picking the right AI tools and building the right infrastructure that they aren’t thinking about what happens when they hit the ice. Even if the technology works as designed, you have no idea whether it will deliver the intended results or create a ripple of unintended consequences that paralyze your business and put egg on your face.

Diagnose Before You Prescribe

The circumstances of AI are different too, and that requires a new playbook. Make that playbooks. Picking the right playbook requires something my clients and I call Calibrated Decision Design.

We start by asking how long it will take to realize the ultimate goals of the investment. Do we need to break even this year, or is this a multi-year bet where results slowly roll in? Most teams have a sense of this, so it allows us to move quickly to the next, much harder question.

What do we know and what do we believe? This is where most teams and AI implementations fail. To seem confident and indispensable, people present hypotheses as if they are facts resulting in decisions based on a single data points or best guesses. The result is a confident decision destined to crumble.

Where you land on these two axes determines your playbook. Apply the wrong one and you’ll either waste money on over-analysis or burn through budget on premature action.

Pick from the Four Playbooks

Go NOW!: You have the facts and need results now. Stop deliberating. Execute.

Predictable Planning: You have confidence in the outcome, but the payoff takes patience. Build a flexible strategy and operational plan to stay responsive as things progress.

Discovery Planning: You need results fast, but you don’t have proof your plan will work. Run small, fast experiments before scaling anything.

Resilient Strategy: The time horizon is long and you’re short on facts. The worst thing you can do is go all in. Instead, envision multiple futures, identify early warning signs, find commonalities and prepare a strategy that can pivot.

Apply it

Which playbook are you using and which one is best for your circumstance?

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 25, 2026 | AI, Leadership, Leading Through Uncertainty

Spain, 1896

At the tender age of 14, Pablo Ruiz Picasso painted a portrait of his Aunt Pepa a work of brilliant academic realism that would go on to be hailed as “without a doubt one of the greatest in the whole history of Spanish painting.”

In 1901, he abandoned his mastery of realism, painting only in shades blue and blue-green.

There’s debate over why Picasso’s Blue Period began. Some argue that it’s a reflection of the poverty and desperation he experienced as a starving artist in Paris. Others claim it was a response to the suicide of his friend, Carles Casagemas. But Bill Gurley, a longtime venture capitalist, has a different theory.

Picasso abandoned realism because of the Kodak Brownie.

Introduced on February 1, 1900, the Kodak Brownie made photography widely available, fulfilling George Eastman’s promise that “you press the button, we do the rest.”

An ocean away, Gurley argues, Picasso’s “move toward abstraction wasn’t a rejection of skill; it was a recognition that realism had stopped being the frontier….So Picasso moved on, not because realism was wrong, but because it was finished.”

Washington DC, 2004

Three years before Drive took the world by storm, Daniel Pink published his third book, A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future.

In it, he argues that a combination of technological advancements, higher standards of living, and access to cheaper labor are pushing us from a world that values left brain skills like linear thought, analysis, and optimization towards one that requires right brain skills like artistry, empathy, and big picture thinking.

As a result, those who succeed in the future will be able to think like designers, tell stories with context and emotional impact, and combine disparate pieces into a whole greater than the sum of its parts. Leaders will need to be empathetic, able to create “a pathway to more intense creativity and inspiration,” and guide others in the pursuit of meaning and significance.

California, 2026

Barry O’Reilly, author of Unlearn, published his monthly blog post, “Six Counterintuitive Trends to Think about for 2026,” in which he outlines what he believes will be the human reactions to a world in which AI is everywhere.

Leadership, he asserts, will cease to be measured by the resources we control (and how well we control them to extract maximum value) but by judgment. Specifically, a leader’s ability to:

- Ask better questions

- Frame decisions clearly

- Hold ambiguity without freezing

- Know when not to use AI

The Price of Safety vs the Promise of Greatness

Picasso walked away from a thriving and lucrative market where he was an emerging star to suffer the poverty, uncertainty, and desperation of finding what was next. It would take more than a decade for him to find international acclaim. He would spend the rest of his life as the most famous and financially successful artist in the world.

Are you willing to take that same risk?

You can cling to the safety of what you know, the markets, industries, business models, structures, incentives that have always worked. You can continue to demand immediate efficiency, obedience, and profit while experimenting with new tech and playing with creative ideas.

Or you can start to build what’s next. You don’t have to abandon what works, just as Picasso didn’t abandon paint. But you do have to start using your resources in new ways. You must build the characteristics and capabilities that Daniel Pink outlines. You must become the “counterintuitive” leader that embraces ambiguity, role models critical thinking, and rewards creativity and risk-taking.

Do you have the courage to be counterintuitive?

Are you willing to embrace your inner Picasso?

by Robyn Bolton | Dec 10, 2025 | Customer Centricity, Innovation, Leading Through Uncertainty

In times of great uncertainty, we seek safety. But what does “safety” look like?

What we say: Safety = Data

We tend to believe that we are rational beings and, as a result, we rely on data to make decisions.

Great! We’ve got lots of data from lots of uncertain periods. HBR examined 4,700 public companies during three global recessions (1980, 1990, and 2000). They found that the companies that the companies that emerged “outperforming rivals in their industry by at least 10% in terms of sales and profits growth” had one thing in common: They aggressively made cuts to improve operational efficiency and ruthlessly invested in marketing, R&D, and building new assets to better serve customers have the highest probability of emerging as markets leaders post-recession.

This research was backed up in 2020 in a McKinsey study that found that “Organizations that maintained their innovation focus through the 2009 financial crisis, for example, emerged stronger, outperforming the market average by more than 30 percent and continuing to deliver accelerated growth over the subsequent three to five years.”

What we do: Safety = Hoarding

The reality is that we are human beings and, as a result, make decisions based on how we feel and the use data to justify those decisions.

How else do you explain that despite the data, only 9% of companies took the balanced approach recommended in the HBR study and, ten years later, only 25% of the companies studied by McKinsey stated that “capturing new growth” was a top priority coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Uncertainty is scary so, as individuals and as organizations, we scramble to secure scarce resources, cut anything that feels extraneous, and shift or focus to survival.

What now? And, not Or.

What was true in 2010 is still true today and new research from Bain offers practical advice for how leaders can follow both their hearts and their heads.

Implement systems to protect you from yourself. Bain studied Fast Company’s 50 Most Innovative Companies and found that 79% use two different operating models for innovation to combat executives’ natural risk aversion. The first, for sustaining innovation uses traditional stage-gate models, seeks input from experts and existing customers, and is evaluated on ROI-driven metrics.

The second, for breakthrough innovations, is designed to embrace and manage uncertainty by learning from new customers and emerging trends, working with speed and agility, engaging non-traditional collaborators, and evaluating projects based on their long-term potential and strategic option value.

Don’t outspend. Out-allocate. Supporting the two-system approach, nearly half of the companies studied send less on R&D than their peers overall and spend it differently: 39% of their R&D budgets to sustaining innovations and 61% to expanding into new categories or business models.

Use AI to accelerate, not create. Companies integrating AI into innovation processes have seen design-to-launch timelines shrink by 20% or more. The key word there is “integrate,” not outsource. They use AI for data and trend analysis, rapid prototyping, and automating repetitive tasks. But they still rely on humans for original thinking, intuition-based decisions, and genuine customer empathy.

Prioritize humans above all else. Even though all the information in the world is at our fingerprints, humans remain unknowable, unpredictable, and wonderfully weird. That’s why successful companies use AI to enhance, not replace, direct engagement with customers. They use synthetic personas as a rehearsal space for brainstorming, designing research, and concept testing. But they also know there is no replacement (yet) for human-to-human interaction, especially when creating new offerings and business models.

In times of great uncertainty, we seek safety. But safety doesn’t guarantee certainty. Nothing does. So, the safest thing we can do is learn from the past, prepare (not plan) for the future, make the best decisions possible based on what we know and feel today, and stay open to changing them tomorrow.

by Robyn Bolton | Dec 2, 2025 | AI

“It just popped up one day. Who knows how long they worked on it or how many of millions were spent. They told us to think of it as ChatGPT but trained on everything our company has ever done so we can ask it anything and get an answer immediately.”

The words my client was using to describe her company’s new AI Chatbot made it sound like a miracle. Her tone said something else completely.

“It sounds helpful,” I offered. “Have you tried it?”

“I’m not training my replacement! And I’m not going to train my R&D, Supply Chain, Customer Insights, or Finance colleagues’ replacements either. And I’m not alone. I don’t think anyone’s using it because the company just announced they’re tracking usage and, if we don’t use it daily, that will be reflected in our performance reviews.”

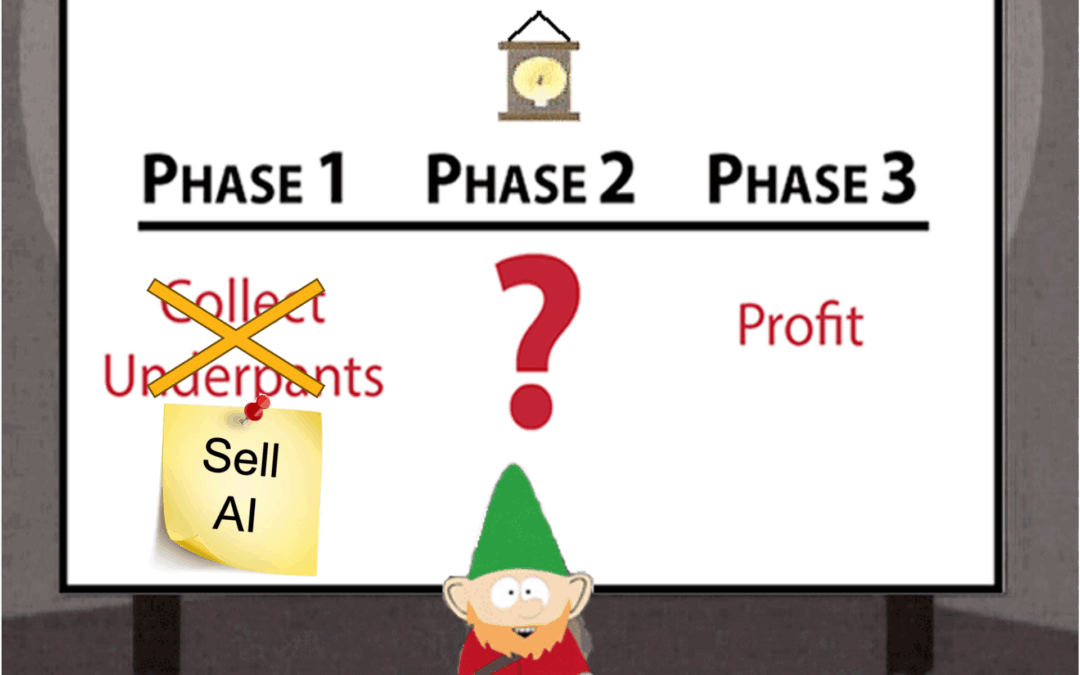

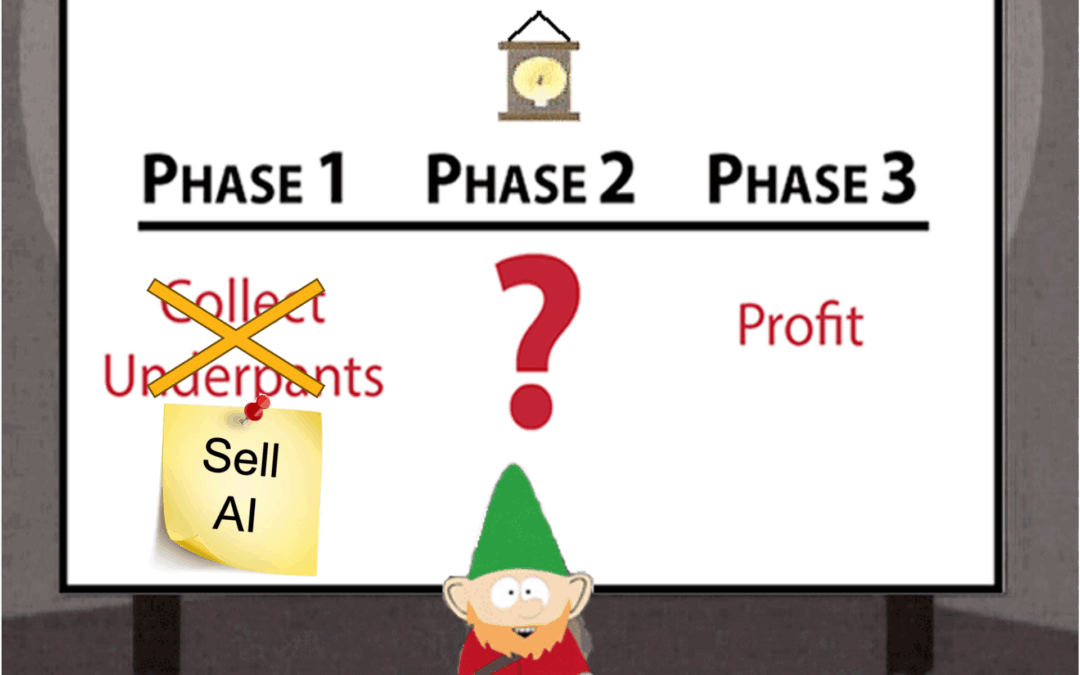

All I could do was sigh. The Underpants Gnomes have struck again.

Who are the Underpants Gnomes?

The Underpants Gnomes are the stars of a 1998 South Park episode described by media critic Paul Cantor as, “the most fully developed defense of capitalism ever produced.”

Claiming to be business experts, the Underpants Gnomes sneak into South Park residents’ homes every night and steal their underpants. When confronted by the boy in their underground lair, the Gnomes explain their business plan:

- Collect underpants

- ?

- Profit

It was meant as satire.

Some took it as a an abbreviated MBA.

How to Spot the Underpants AI Gnomes

As the AI hype grows, fueling executive FOMO (Fear of Missing Out), the Underpants Gnomes, cleverly disguised as experts, entrepreneurs and consultants, saw their opportunity.

- Sell AI

- ?

- Profit

While they’ve pivoted their business focus, they haven’t improved their operations so the Underpants AI Gnomes as still easy to spot:

- Investment without Intention: Is your company investing in AI because it’s “essential to future-proofing the business?” That sounds good but if your company can’t explain the future it’s proofing itself against and how AI builds a moat or a life preserver in that future, it’s a sign that the Gnomes are in the building.

- Switches, not Solutions: If your company thinks that AI adoption is as “easy as turning on Copilot” or “installing a custom GPT chatbot, the Gnomes are gaining traction. AI is a tool and you need to teach people how to use tools, build processes to support the change, and demonstrate the benefit.

- Activity without Achievement: When MIT published research indicating that 95% of corporate Gen AI pilots were failing, it was a sign of just how deeply the Gnomes have infiltrated companies. Experiments are essential at the start of any new venture but only useful if they generate replicable and scalable learning.

How to defend against the AI Gnomes

Odds are the gnomes are already in your company. But fear not, you can still turn “Phase 2:?” into something that actually leads to “Phase 3: Profit.”

- Start with the end in mind: Be specific about the outcome you are trying to achieve. The answer should be agnostic of AI and tied to business goals.

- Design with people at the center: Achieving your desired outcomes requires rethinking and redesigning existing processes. Strategic creativity like that requires combining people, processes, and technology to achieve and embed.

- Develop with discipline: Just because you can (run a pilot, sign up for a free trial), doesn’t mean you should. Small-scale experiments require the same degree of discipline as multi-million-dollar digital transformations. So, if you can’t articulate what you need to learn and how it contributes to the bigger goal, move on.

AI, in all its forms, is here to stay. But the same doesn’t have to be true for the AI Gnomes.

Have you spotted the Gnomes in your company?