by Robyn Bolton | Oct 6, 2025 | 5 Questions, Customer Centricity, Innovation, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

For decades, we’ve faithfully followed innovation’s best practices. The brainstorming workshops, the customer interviews, and the validated frameworks that make innovation feel systematic and professional. Design thinking sessions, check. Lean startup methodology, check. It’s deeply satisfying, like solving a puzzle where all the pieces fit perfectly.

Problem is, we’re solving the wrong puzzle.

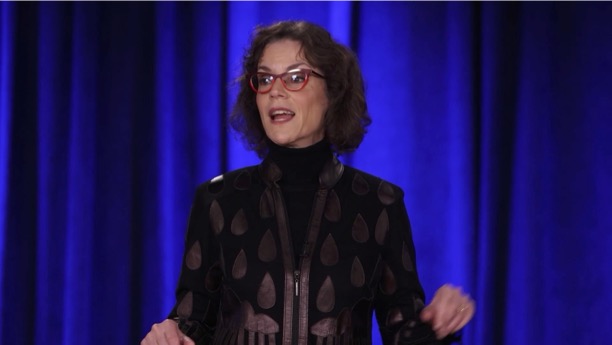

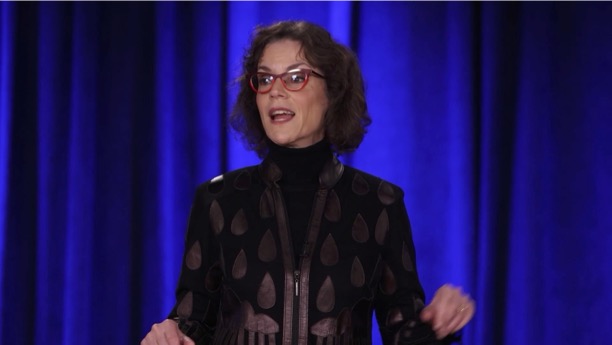

As Ellen Di Resta points out in this conversation, all the frameworks we worship, from brainstorming through business model mapping, are business-building tools, not idea creation tools.

Read on to learn why our failure to act on the fundamental distinction between value creation and value capture causes too many disciplined, process-following teams to create beautiful prototypes for products nobody wants.

Robyn: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about innovation that organizations need to unlearn?

Ellen: That the innovation best practices everyone’s obsessed with work for the early stages of innovation.

The early part of the innovation process is all about creating value for the customer. What are their needs? Why are their Jobs to be Done unsatisfied? But very quickly we shift to coming up with an idea, prototyping it, and creating a business plan. We shift to creating value for the business, before we assess whether or not we’ve successfully created value for the customer.

Think about all those innovation best practices. We’ve got business model canvas. That’s about how you create value for the business. Right? We’ve got the incubators, accelerators, lean, lean startup. It’s about creating the startup, which is a business, right? These tools are about creating value for the business, not the customer.

R: You know that Jobs to be Done is a hill I will die on, so I am firmly in the camp that if it doesn’t create value for the customer, it can’t create value for the business. So why do people rush through the process of creating ideas that create customer value?

E: We don’t really teach people how to develop ideas because our culture only values what’s tangible. But an idea is not a tangible thing so it’s hard for people to get their minds around it. What does it mean to work on it? What does it mean to develop it? We need to learn what motivates people’s decision-making.

Prototypes and solutions are much easier to sell to people because you have something tangible that you can show to them, explain, and answer questions about. Then they either say yes or no, and you immediately know if you succeeded or failed.

R: Sounds like it all comes down to how quickly and accurately can I measure outcomes?

E: Exactly. But here’s the rub, they don’t even know they’re rushing because traditional innovation tools give them a sense of progress, even if the progress is wrong.

We’ve all been to a brainstorm session, right? Somebody calls the brainstorm session. Everybody goes. They say any idea is good. Nothing is bad. Come up with wild, crazy ideas. They plaster the walls with 300 ideas, and then everybody leaves, and they feel good and happy and creative, and the poor person who called the brainstorm is stuck.

Now what do they do? They look at these 300 ideas, and they sort them based on things they can measure like how long it’ll take to do or how much money it’ll cost to do it. What happens? They end up choosing the things that we already know how to do! So why have the brainstorm?”

R: This creates a real tension: leadership wants progress they can track, but the early work is inherently unmeasurable. How do you navigate that organizational reality?

E: Those tangible metrics are all about reliability. They make sure you’re doing things right. That you’re doing it the same way every time? And that’s appropriate when you know what you’re doing, know you’re creating value for the customer, and now you’re working to create value for the business. Usually at scale

But the other side of it? That’s where you’re creating new value and you are trying to figure things out. You need validity metrics. Are we doing the right things? How will we know that we’re doing the right things.

R: What’s the most important insight leaders need to understand about early-stage innovation?

E: The one thing that the leader must do is run cover. Their job is to protect the team who’s doing the actual idea development work because that work is fuzzy and doesn’t look like it’s getting anywhere until Ta-Da, it’s done!

They need to strategically communicate and make sure that the leadership hears what they need to hear, so that they know everything is in control, right? And so they’re running cover is the best way to describe it. And if you don’t have that person, it’s really hard to do the idea development work.”

But to do all of that, the leader also must really care about that problem and about understanding the customer.

We must create value for the customer before we can create value for the business. Ellen’s insight that most innovation best practices focus on the latter is devastating. It’s also essential for all the leaders and teams who need results from their innovation investments.

Before your next innovation project touches a single framework, ask yourself Ellen’s fundamental question: “Are we at a stage where we’re creating value for the customer, or the business?” If you can’t answer that clearly, put down the canvas and start having deeper conversations with the people whose problems you think you’re solving.

To learn more about Ellen’s work, check out Pearl Partners.

To dive deeper into Ellen’s though leadership, visit her Substack – Idea Builders Guild.

To break the cycle of using the wrong idea tools, sign-up for her free one-hour workshop.

by Robyn Bolton | Sep 23, 2025 | Innovation, Metrics, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

It’s time for your company’s All-Hands meeting. Your CEO stands on stage and announces ambitious innovation goals, talking passionately about the importance of long-term thinking and breakthrough results. Everyone nods enthusiastically, applauds politely, and returns to their desks to focus on hitting this quarter’s numbers. After all, that’s what their bonuses depend on.

Kate Dixon, compensation expert and founder of Dixon Consulting, has watched this contradiction play out across Fortune 500 companies, B Corps, and startups. Her insight cuts to the heart of why so many innovation initiatives fail: we’re asking people to think long-term while paying them to deliver short-term.

In our conversation, Kate revealed why most companies are inadvertently sabotaging their own innovation efforts through their compensation structures—and what the smartest organizations are doing differently.

Robyn Bolton: Kate, when I first heard you say, “compensation is the expression of a company’s culture,” it blew my mind. What do you mean by that?

Kate Dixon: If you want to understand what an organization values, look at how they pay their people: Who gets paid more? Who gets paid less? Who gets bigger bonuses? Who moves up in the organization and who doesn’t? Who gets long-term incentives?

The answers to these questions, and a million others, express the culture of the organization. How we reward people’s performance, either directly or indirectly, establishes and reinforces cultural norms. Compensation is usually the biggest, if not the biggest, expenses that a company has so they’re very thoughtful and deliberate about how it is used. Which is why it tells you what the company actually does value.

RB: What’s the biggest mistake companies make when trying to incentivize innovation?

KD: Let’s start by what companies are good at when it comes to compensations and incentives. They’re really good about base pay, because that’s the biggest part of pay for most people in an organization. Then they spend the next amount of time and effort trying to figure out the annual bonus structure. After that comes other benefits, like long term incentives, assuming they don’t fall by the wayside.

As you know, innovation can take a long time to payout, so long-term incentives are key to encouraging that kind of investment. Stock options and restricted shares are probably the most common long-term incentives but cash bonuses, phantom stock, and ESOP shares in employee-owned companies are also considered long term incentives.

Large companies are pretty good using some equity as an incentive, but they tie it t long term revenue goals, not innovation. As you often remind us, “innovation is a means to the end, which is growth,” so tying incentives to growth isn’t bad but I believe that we can do better. Tying incentives to the growth goals and how they’re achieved will go a long way towards driving innovation.

RB: I’ve worked in and with big companies and I’ve noticed that while they say, “innovation is everyone’s job,” the people who get long-term incentives are typically senior execs. What gives?

Long-term incentives are definitely underutilized, below the executive level, and maybe below the director level. Assuming that most companies’ innovation efforts aren’t moonshots that take decades to realize, it makes a ton of sense to use long-term incentives throughout the organization and its ecosystem. However, when this idea is proposed, people often pushback because “it’s too complex” for folks lower in the organization, “they wouldn’t understand.” or “they won’t appreciate it”. That stance is both arrogant and untrue. I’ve consistently seen that when you explain long-term incentives to people, they do get it, it does motivate them, and the company does see results.

RB: Are there any examples of organizations that are getting this right?

We’re seeing a lot more innovative and interesting risk-taking behaviors in companies that are not primarily focused on profit.

Our B Corp clients are doing some crazy, cool stuff. We have an employee-owned company that is a consulting firm, but they had an idea for a software product. They launched it and now it’s becoming a bigger and bigger part of their business.

Family-owned or public companies that have a single giganto shareholder are also hotbeds of long-term thinking and, therefore, innovation. They don’t have that same quarter to quarter pressure that drives a relentless focus on what’s happening right now and allows people to focus on the future.

What’s the most important thing leaders need to understand about compensation and innovation?

If you’re serious about innovation, you should be incentivizing people all over the organization. If you want innovation to be a more regular piece of the culture so you get better results, you’ve got to look at long term incentives. Yes, you should reward people for revenue and short-term goals. But you also need to consider what else is a precursor to our innovation. What else is makes the conditions for innovating better for people, and reward that, too.

Kate’s insight reveals the fundamental contradiction at the heart of most companies’ innovation struggles: you can’t build long-term value with short-term thinking, especially when your compensation system rewards only the latter.

What does your company’s approach to compensation say about its culture and values?

by Robyn Bolton | Jul 28, 2025 | 5 Questions, Leadership

Picture this: your boss announces a major reorganization with a big smile, expecting you to be excited about “new opportunities.” Meanwhile, you’re sitting there thinking “What the hell just happened to my job?”

Theresa Ward, founder and Chief Momentum Officer of Fiery Feather, has spent years watching this disconnect play out. Her insight? Leaders are expected to sell change while still personally struggling with it, creating what she calls “that weird middle ground” where authenticity goes to die.

Our conversation revealed why unwelcome change triggers the same response as grief, and why leaders who stop pretending they’ve got it figured out are more successful.

Robyn Bolton: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about leading change that organizations need to unlearn?

Theresa Ward: That middle managers need to be enthusiastic about a change, or at least appear enthusiastic, to lead their teams through it.

RB: It seems like enthusiasm is important to get people on board and doing what they need to do to make change happen. Why is this wrong?

TW: Because it makes you wonder if this person is being authentic. Are they genuinely enthusiastic? Do they really believe this is the right thing?

To be clear, I’m talking about Unwelcome Change. Change that is thrust upon you. How we experience Unwelcome Change is the same way we experience grief.

When we initially experience Unwelcome Change, our brain goes into shock or denial which can actually trigger an increase in engagement and productivity.

Then we move into anger and blame, which looks different for all of us. We’ve probably experienced somebody yelling in a meeting, but it can also look like turning off the camera, folding your arms, rolling your eyes, and disengaging.

Bargaining. I always think of that clip from Jerry Maguire, where he’s got the goldfish, and he says, “Who’s coming with me?” because he’s going to make lemonades out of this lemon, even if it’s a completely ridiculous condition.

Then depression sets in. It’s the low point but it’s also where you’re really ready to admit that you’re upset, sad, and grieving the change that has happened. It’s the dark before the dawn.

RB: If everyone goes through this grief process, why do some leaders seem genuinely enthusiastic about the change?”

TW: If they came up with the idea, they’re not going to be angry or depressed about their own idea.

But even if it’s one announcement, people don’t experience just one change. It’s not, “Our budget is going from X to Y” and everyone can just get used to it. It’s double or triple that! It’s a budget cut, then a reorg, then a new boss, then a friend being laid off, then a project you loved getting trashed. You’re dealing with onion layers of change.

We all go through different stages at speeds. You can’t rush it. Sometimes you just have to be like, “Oh, okay, I’m feeling pretty angry this week. I’m just gonna have to sit through my anger phase and realize that it’s a phase.”

RB: I get that you can’t rush the process, but change doesn’t slow down so you can catch up. What can people do to navigate change while they’re processing it?

TW: BLT, baby. These are 3 tools, not a formula, that you can use for different experiences.

B stands for Benefit of Change. This is finding the silver lining, something we often underestimate because it’s such a broad cliche. For it to be effective, you need to look for a specific and personal silver lining. For example, a friend of mine works for a company that was acquired. He was not a fan of how the culture was changing, but the bigger company offered tuition reimbursement. So he used that to get his master’s of fine arts for free.

L is Locus of Control. Take inventory of everything that’s upsetting you and place it into one of 3 categories: What can I control? What can I influence? What do I need to just surrender? Sitting up at night and worrying about whether the budget will be cut again is outside of my control. So, I shouldn’t spend my time and energy on that. Instead, I need to focus on what I can control, like my attitude and response.

T is Take the Long View. Every day we find ourselves in situations that get us emotional – a traffic jam, getting cut off in traffic, or flubbing a big client presentation. When we get more emotional than what the situation calls for, ask how you’re going to feel about the situation tomorrow, then in a month, then a year Because when our fight or flight brain mode kicks in, we catastrophize things. But the reality is that most of it won’t matter tomorrow.

RB: What’s the most important mindset shift leaders need to make to help their teams through unwelcome change?

TW: Find what works for you first then, with empathy, help your team. Like the Airline Safety Video, put your mask on first, then help others. It allows you to be authentic and builds empathy with the team. Two things required to start the shift from unwelcome to accepted.

Theresa’s BLT framework won’t make change painless, but it gives you permission to admit that transformation is hard, even for leaders. The moment you stop pretending you’ve got it all figured out is the moment your team starts trusting you to guide them through the mess.

by Robyn Bolton | May 30, 2025 | Leadership, Strategy

Conventional wisdom tells us that transformation flows from the C-suite down because real change requires executive mandates and company-wide rollouts. But what if our focus on building transformation momentum is exactly backward?

Ever since reading Multipliers, where Liz Wiseman revealed how the best leaders amplify their people rather than diminish them, I’ve wondered if, like innovation, organizational transformation and change also require us to do the opposite of our instincts.

I recently had the opportunity to dig deeper into this topic with her, and I couldn’t resist exploring how change really happens in large organizations.

What emerged wasn’t another framework—it was something more brilliant and subversive: how middle managers quietly become change agents, why sustainable transformation looks nothing like a launch event, and the liberating truth that leaders don’t need to be perfect.

Robyn Bolton: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about leading change that you believe organizations need to unlearn?

Lize Wiseman: I don’t believe that change needs to start, or even be sponsored, at the top of the organization. I’ve seen so much change led from the middle management ranks. When middle managers experiment with new mindsets and practices inside their organizations, they produce pockets of success—anomalies that catch the attention of senior executives and corporate staffers who are highly adept at detecting variances (both negative and positive). When senior executives notice positive outcomes, they are quick to elevate and endorse the new practices, in turn spreading the practices to other parts of the organization. In other words, most senior executives are adept at spotting a parade and getting in front of it! (Incidentally, this is one of several executive skills you won’t find documented on any official leadership competency model.) If you don’t yet have the political capital to lead a company-wide initiative, run a pilot with a few rising middle managers. Shine a spotlight on their success and let the practices spread to their peers. Expose their good work to the executive team and make yourself available to turn the parade into a movement.

RB: In your research and work, what’s the most surprising pattern you’ve observed about successful organizational transformation?”

LW: As mentioned above, I believe the starting point for transformation is less important than how you will sustain the momentum you’ve generated. Unfortunately, most new initiatives—be they corporate change initiatives or personal improvement plans—begin with a bang but fizzle out in what I call “the failure to launch” cycle. Transformation that is sustained over time usually starts small and builds a series of successive wins. Each win provides the energy needed to carry the work into the next phase. These series of wins generate the energy and collective will needed to complete the cycle of success. As that cycle spins, nascent beliefs become more deeply entrenched and old survival strategies get supplanted by new methods to not just survive but thrive inside the organization.

Each little success requires careful support and an evidence-backed PR campaign to build awareness and broad support for the new direction. Nascent behavior and beliefs are fragile and will be overpowered by older assumptions until they are strengthened by supporting evidence. The supporting evidence forms a buttress around the budding mindset or practices, much like a brace around a sapling provides stability until the tree is strong enough to stand on its own.

RB: How has your thinking about what makes an effective leader evolved over the course of your career?

LW: When I began researching good leadership, most diminishing leaders appeared to be tyrannical, narcissistic bullies. But as I further studied the problem, I’ve come to see that the vast majority of the diminishing happening inside our workplaces is done with the best of intentions, by what I call the Accidental Diminisher—good people trying to be good managers. I’ve become less interested in knowing who is a Diminisher and much more interested in understanding what provokes the Diminisher tendencies that lurk inside each of us.

RB: When you consider all the organizations you’ve studied, what’s the most powerful lesson about driving meaningful change that most leaders overlook?

LW: One of the dangers of trying to lead change from the top is that most leaders have a hard time being a constant role model for the changes they advocate for. Even the best leaders can’t always display the positive behaviors they espouse and ask their organizations to embody. It’s human to slip up. But when behavior change is led primarily from the top, these all-too-natural slip-ups can become major setbacks for the whole organization because they provide visible evidence that the new behavior isn’t required or feasible, and followers can easily give up. Wise leaders understand this dynamic and build a hypocrisy factor into their change plans–meaning, they acknowledge upfront that they aspire to the new behavior but don’t always fully embody it, yet. They set the expectation that there will be setbacks and invite people to help them be better leaders as well. They acknowledge that the route to new behavior typically looks like the acclimation process used by high-elevation climbers. These climbers spend some of their days in ascent, but once they reach new elevations, often have to descend to lower camps to acclimate. It’s the proverbial two-steps-forward, one-step-back process. When leaders acknowledge their shortcomings and the likelihood of their future missteps, they not only minimize the chance that others give up when they see hypocrisy above them, but they create space for others to make and recover from their own mistakes.

RB: Looking ahead, what do you believe is the most important capability leaders need to develop to help their organizations thrive?

LW: Leading in uncertainty, specifically the ability to lead people to destinations that they themselves have never been.

I love that Liz’s insights flip the script, calling on people outside the C-Suite to stop waiting for permission and start running quiet experiments, building proof points, and letting success do the selling.

The next time you want a change or have change thrust upon you, don’t look for a parade to lead. Look for one person willing to try something different and get to work.

by Robyn Bolton | May 10, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership

You need friction to create fire. It’s true whether you’re camping or leading change inside an organization. Yet most of us avoid conflict—we ignore it, smooth it over, or sideline the people who spark it.

I’ve been guilty of that too, which is why I was eager to sit down with Laura Weiss, founder of Design Diplomacy, former architect and IDEO partner, university educator, and professional mediator, to explore why conflict isn’t the enemy of innovation, but one of its essential ingredients.

Our conversation wasn’t about frameworks or facilitation tricks. It was about something deeper: how leaders can unlearn their fear of conflict, lean into discomfort, and use it to build trust, fuel learning, and drive meaningful change.

So if conflict feels like a threat to alignment and progress, this conversation will show you why embracing it is the real leadership move.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Robyn Bolton: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about change that organizations need to unlearn?

Laura Weiss: The belief that change is event-driven. It’s not, except for seismic shifts like the Great Recession, the COVID-19 pandemic, 9/11, and October 7. It’s happening all the time! As a result, leading change should be seen as a continuous endeavor that prepares the organization to be agile when unforeseen events occur.

RB: Wow, that is capital-T True! What is driving this misperception?

LW: It’s been said that ‘managers deal with complexity, but leaders deal with change’. So, it all comes down to leadership. However, the prevailing belief is that a “leader” is the person who has risen to the top of the organization and has all the answers.

In many design professions, those who are promoted to leadership roles are exceptional at their craft. But evolving from an ‘individual contributor’ to leading others involves skills that can seem contrary to our beliefs about leadership. One is humility – the capability to say “I don’t know” without feeling exposed as a fraud, especially in professions where being a “subject matter expert” is expected. Being humble presents the leader as human, which leads to another skill: connecting with others as humans before attempting to ‘lead’ them. I particularly like Edgar Schein’s relationship-driven leadership philosophy as opposed to ‘transactional’ leadership, where your role relative to others dictates how you interact.

RB: From your experience, how can we unlearn this and lead differently?

LW: Leaders need to do three things:

- Be self-aware. After becoming a certified coach, it became clear to me that all leadership begins with understanding oneself. If you’re unaware of how you operate in the world, you certainly can’t lead others effectively.

- Be agile. Machiavelli famously asked: “Is it better to be loved or feared…?” Being a leader requires the ability to do both, operating along the ‘warmth-strength’ continuum, starting with warmth. There are six leadership styles a leader should be familiar with, in the same way that golfers know which golf club to use for a particular situation.

- Evolve. This means feedback – being willing to ask for it and receive it. Many senior leaders stop receiving feedback as they progress in their careers. But times change, and ‘what got you here won’t get you there.’ Holding up a mirror to very senior leaders who have rarely, if ever, received feedback, or have received it but didn’t really “get it,” is critical if they are to change with the times and the needs of their organization.

RB: Amen! I’m starting to sense a connection between leadership, innovation, and change, but before I make assumptions, what do you see?

LW: First, I want to acknowledge the thesis of your book that “innovation isn’t an idea problem, it’s a leadership problem” – 1000% agree with that!

One of the reasons I shifted from being an architect to focusing on the broader world of innovation was that I was curious about why some innovation initiatives were successful and some were not. Specifically, I was curious about the role of conflict in the creative problem-solving process because conflict is critical to bringing innovation and change to life. Yet, it’s not something most of us are naturally good at – in fact, our brain is designed to avoid it!

The biggest myth about conflict is that it erodes trust and undermines relationships. The opposite is true – when handled well, productive conflict strengthens relationships and leads to better outcomes for organizations navigating change.

Just as with innovation, the organizations that are most successful with change are the ones that consistently use productive conflict as an enabler of change.

To achieve this, organizations must shift from a reactive stance to a proactive one and become more “discovery-driven”. This means practicing iterative prototyping and learning their way forward. In my mind, innovation is a form of structured learning that yields something new with value.

RB: What role does communication play in leadership and conflict?

LW: Conflict is an inevitable part of the human experience because it reflects the tension between the status quo and something else that’s trying to emerge. It can appear even in the process of solving daily problems, so the ability to deal productively with conflict, from simple misunderstandings to seemingly intractable differences, is crucial.

The source code for effective conflict engagement is effective conversations.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

The real challenge in leadership isn’t preventing conflict—it’s recognizing that conflict is already happening and choosing to engage with it productively through conversation

This conversation with Laura reminded me that innovation and change don’t just thrive on new ideas. They require leaders who are self-aware enough to listen, humble enough to ask for feedback, and courageous enough to stay in the tension long enough for something better to emerge.