5 Questions: Liz Wiseman on Building Transformation Momentum from the Middle

Conventional wisdom tells us that transformation flows from the C-suite down because real change requires executive mandates and company-wide rollouts. But what if our focus on building transformation momentum is exactly backward?

Ever since reading Multipliers, where Liz Wiseman revealed how the best leaders amplify their people rather than diminish them, I’ve wondered if, like innovation, organizational transformation and change also require us to do the opposite of our instincts.

I recently had the opportunity to dig deeper into this topic with her, and I couldn’t resist exploring how change really happens in large organizations.

What emerged wasn’t another framework—it was something more brilliant and subversive: how middle managers quietly become change agents, why sustainable transformation looks nothing like a launch event, and the liberating truth that leaders don’t need to be perfect.

Robyn Bolton: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about leading change that you believe organizations need to unlearn?

Lize Wiseman: I don’t believe that change needs to start, or even be sponsored, at the top of the organization. I’ve seen so much change led from the middle management ranks. When middle managers experiment with new mindsets and practices inside their organizations, they produce pockets of success—anomalies that catch the attention of senior executives and corporate staffers who are highly adept at detecting variances (both negative and positive). When senior executives notice positive outcomes, they are quick to elevate and endorse the new practices, in turn spreading the practices to other parts of the organization. In other words, most senior executives are adept at spotting a parade and getting in front of it! (Incidentally, this is one of several executive skills you won’t find documented on any official leadership competency model.) If you don’t yet have the political capital to lead a company-wide initiative, run a pilot with a few rising middle managers. Shine a spotlight on their success and let the practices spread to their peers. Expose their good work to the executive team and make yourself available to turn the parade into a movement.

RB: In your research and work, what’s the most surprising pattern you’ve observed about successful organizational transformation?”

LW: As mentioned above, I believe the starting point for transformation is less important than how you will sustain the momentum you’ve generated. Unfortunately, most new initiatives—be they corporate change initiatives or personal improvement plans—begin with a bang but fizzle out in what I call “the failure to launch” cycle. Transformation that is sustained over time usually starts small and builds a series of successive wins. Each win provides the energy needed to carry the work into the next phase. These series of wins generate the energy and collective will needed to complete the cycle of success. As that cycle spins, nascent beliefs become more deeply entrenched and old survival strategies get supplanted by new methods to not just survive but thrive inside the organization.

Each little success requires careful support and an evidence-backed PR campaign to build awareness and broad support for the new direction. Nascent behavior and beliefs are fragile and will be overpowered by older assumptions until they are strengthened by supporting evidence. The supporting evidence forms a buttress around the budding mindset or practices, much like a brace around a sapling provides stability until the tree is strong enough to stand on its own.

RB: How has your thinking about what makes an effective leader evolved over the course of your career?

LW: When I began researching good leadership, most diminishing leaders appeared to be tyrannical, narcissistic bullies. But as I further studied the problem, I’ve come to see that the vast majority of the diminishing happening inside our workplaces is done with the best of intentions, by what I call the Accidental Diminisher—good people trying to be good managers. I’ve become less interested in knowing who is a Diminisher and much more interested in understanding what provokes the Diminisher tendencies that lurk inside each of us.

RB: When you consider all the organizations you’ve studied, what’s the most powerful lesson about driving meaningful change that most leaders overlook?

LW: One of the dangers of trying to lead change from the top is that most leaders have a hard time being a constant role model for the changes they advocate for. Even the best leaders can’t always display the positive behaviors they espouse and ask their organizations to embody. It’s human to slip up. But when behavior change is led primarily from the top, these all-too-natural slip-ups can become major setbacks for the whole organization because they provide visible evidence that the new behavior isn’t required or feasible, and followers can easily give up. Wise leaders understand this dynamic and build a hypocrisy factor into their change plans–meaning, they acknowledge upfront that they aspire to the new behavior but don’t always fully embody it, yet. They set the expectation that there will be setbacks and invite people to help them be better leaders as well. They acknowledge that the route to new behavior typically looks like the acclimation process used by high-elevation climbers. These climbers spend some of their days in ascent, but once they reach new elevations, often have to descend to lower camps to acclimate. It’s the proverbial two-steps-forward, one-step-back process. When leaders acknowledge their shortcomings and the likelihood of their future missteps, they not only minimize the chance that others give up when they see hypocrisy above them, but they create space for others to make and recover from their own mistakes.

RB: Looking ahead, what do you believe is the most important capability leaders need to develop to help their organizations thrive?

LW: Leading in uncertainty, specifically the ability to lead people to destinations that they themselves have never been.

I love that Liz’s insights flip the script, calling on people outside the C-Suite to stop waiting for permission and start running quiet experiments, building proof points, and letting success do the selling.

The next time you want a change or have change thrust upon you, don’t look for a parade to lead. Look for one person willing to try something different and get to work.

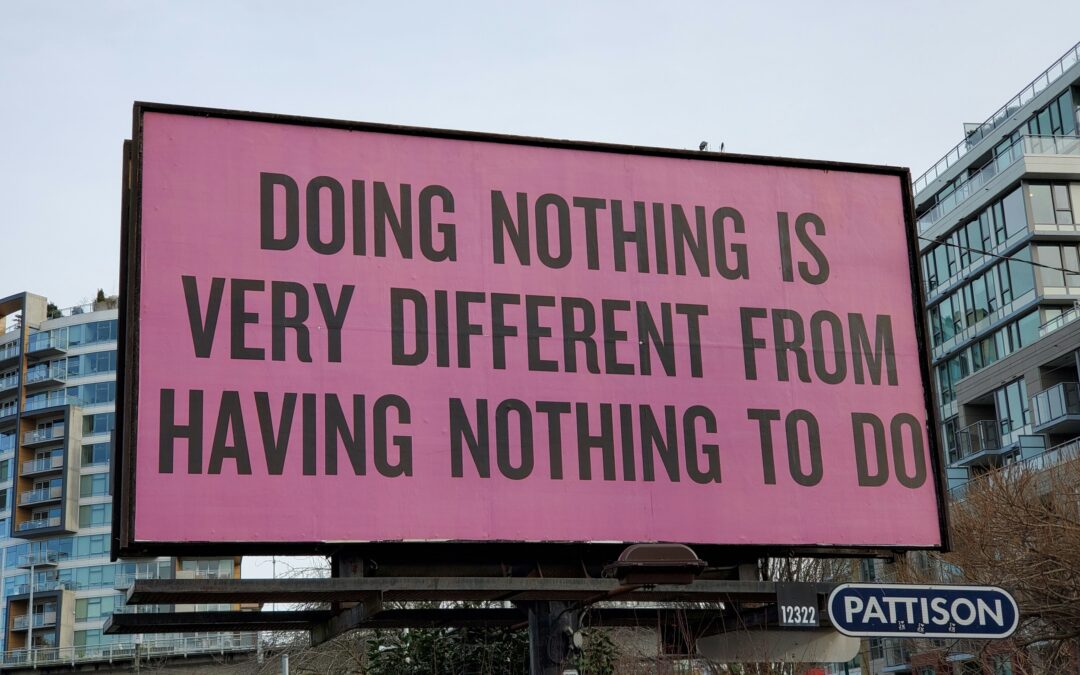

Three Ways Strategic Idleness Gives You an Edge in Driving Innovation and Growth

“What will you do on vacation?” a colleague asked.

“Nothing,” I replied.

The uncomfortable silence that followed spoke volumes. In boardrooms and during quarterly reviews, we celebrate constant motion and back-to-back calendars. Yet, study after study shows that the most successful leaders embrace a counterintuitive edge: strategic idleness.

While your competitors exhaust themselves in perpetual busyness, research shows that deliberate mental downtime activates the brain networks responsible for strategic foresight, innovative solutions, and clear decision-making.

The Status Trap of Busy-ness

At one company I worked with, there was only one acceptable answer to “How are you doing?” “Busy.” The answer wasn’t a way to avoid an awkward hallway conversation. It was social currency. If you’re busy, you’re valuable. If you’re fine, you’re expendable.

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Consumer Research confirmed what Columbia, Georgetown, and Harvard researchers discovered: being busy is now a status symbol, signaling “competence, ambition, and scarcity in the market.”

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: your packed schedule is undermining the very outcomes you’re accountable for delivering.

Your Brain’s Innovation Engine

Neuroscience has confirmed what innovators have long practiced: Strategic Idleness. While you consciously “do nothing,” your default mode network (DMN) engages, making unexpected connections across stored information and experiences.

Recent research published in the journal Brain demonstrates that the DMN is activated during creative thinking, with a specific pattern of neural activity occurring during the search for novel ideas. This network is essential for both spontaneous thought and divergent thinking, core elements of innovation.

So if you’ve always wondered why you get your best ideas in the shower, it’s because your DMN is powered all the way up.

Three Ways to Power-Up Your Engine

Here are three executive-grade approaches to strategic idleness without more showers or productivity sacrifices:

- Pause for 10 Minutes Before Making a Decision

Before making high-stakes decisions, implement a mandatory 10-minute idleness period. No email, no conversation—just sitting. Research on cognitive recovery suggests that this brief reset activates your DMN, allowing for a more comprehensive consideration of variables and strategic implications. - Take a Walking Meeting with Yourself

Block 20 minutes in your calendar each week for a solo walking meeting (and then take the walk!). No other attendees, no agenda, just walking. Researchers at Stanford University found that walking increases creative output by an average of 60% compared to sitting. The combination of physical movement and mental space creates ideal conditions for your brain to generate solutions to problems you didn’t know you had. - Schedule 3-5 minutes of Strategic Silence before key discussions

Research on group dynamics shows that silent reflection before discussion can reduce groupthink and increase the quality of ideas by helping team members process information more deeply. Before you dive into a critical topic at your next leadership meeting, schedule 3-5 minutes of silence. Explain that this silence is for individual reflection and planning for the upcoming discussion, not for checking email or taking bathroom breaks. Acknowledge that it will feel awkward, but that it’s critical for the upcoming discussion and decision.

Remember, You’re Not Doing Nothing If You’re being Strategically Idle

The most valuable asset in your organization isn’t technology, capital, or even the products you sell. It’s the quality of thinking that goes into critical decisions. Strategic idleness isn’t inaction; it’s the deliberate cultivation of conditions that foster innovation, clear judgment, and strategic foresight.

While your competitors remain trapped in perpetual busyness, by using executive advantage of strategic idleness, your next breakthrough will present itself.

This is an updated version of the June 9, 2019, post, “Do More Nothing.”

5 Questions: Laura Weiss on Innovation, Leadership, and Productive Conflict

You need friction to create fire. It’s true whether you’re camping or leading change inside an organization. Yet most of us avoid conflict—we ignore it, smooth it over, or sideline the people who spark it.

I’ve been guilty of that too, which is why I was eager to sit down with Laura Weiss, founder of Design Diplomacy, former architect and IDEO partner, university educator, and professional mediator, to explore why conflict isn’t the enemy of innovation, but one of its essential ingredients.

Our conversation wasn’t about frameworks or facilitation tricks. It was about something deeper: how leaders can unlearn their fear of conflict, lean into discomfort, and use it to build trust, fuel learning, and drive meaningful change.

So if conflict feels like a threat to alignment and progress, this conversation will show you why embracing it is the real leadership move.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Robyn Bolton: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about change that organizations need to unlearn?

Laura Weiss: The belief that change is event-driven. It’s not, except for seismic shifts like the Great Recession, the COVID-19 pandemic, 9/11, and October 7. It’s happening all the time! As a result, leading change should be seen as a continuous endeavor that prepares the organization to be agile when unforeseen events occur.

RB: Wow, that is capital-T True! What is driving this misperception?

LW: It’s been said that ‘managers deal with complexity, but leaders deal with change’. So, it all comes down to leadership. However, the prevailing belief is that a “leader” is the person who has risen to the top of the organization and has all the answers.

In many design professions, those who are promoted to leadership roles are exceptional at their craft. But evolving from an ‘individual contributor’ to leading others involves skills that can seem contrary to our beliefs about leadership. One is humility – the capability to say “I don’t know” without feeling exposed as a fraud, especially in professions where being a “subject matter expert” is expected. Being humble presents the leader as human, which leads to another skill: connecting with others as humans before attempting to ‘lead’ them. I particularly like Edgar Schein’s relationship-driven leadership philosophy as opposed to ‘transactional’ leadership, where your role relative to others dictates how you interact.

RB: From your experience, how can we unlearn this and lead differently?

LW: Leaders need to do three things:

- Be self-aware. After becoming a certified coach, it became clear to me that all leadership begins with understanding oneself. If you’re unaware of how you operate in the world, you certainly can’t lead others effectively.

- Be agile. Machiavelli famously asked: “Is it better to be loved or feared…?” Being a leader requires the ability to do both, operating along the ‘warmth-strength’ continuum, starting with warmth. There are six leadership styles a leader should be familiar with, in the same way that golfers know which golf club to use for a particular situation.

- Evolve. This means feedback – being willing to ask for it and receive it. Many senior leaders stop receiving feedback as they progress in their careers. But times change, and ‘what got you here won’t get you there.’ Holding up a mirror to very senior leaders who have rarely, if ever, received feedback, or have received it but didn’t really “get it,” is critical if they are to change with the times and the needs of their organization.

RB: Amen! I’m starting to sense a connection between leadership, innovation, and change, but before I make assumptions, what do you see?

LW: First, I want to acknowledge the thesis of your book that “innovation isn’t an idea problem, it’s a leadership problem” – 1000% agree with that!

One of the reasons I shifted from being an architect to focusing on the broader world of innovation was that I was curious about why some innovation initiatives were successful and some were not. Specifically, I was curious about the role of conflict in the creative problem-solving process because conflict is critical to bringing innovation and change to life. Yet, it’s not something most of us are naturally good at – in fact, our brain is designed to avoid it!

The biggest myth about conflict is that it erodes trust and undermines relationships. The opposite is true – when handled well, productive conflict strengthens relationships and leads to better outcomes for organizations navigating change.

Just as with innovation, the organizations that are most successful with change are the ones that consistently use productive conflict as an enabler of change.

To achieve this, organizations must shift from a reactive stance to a proactive one and become more “discovery-driven”. This means practicing iterative prototyping and learning their way forward. In my mind, innovation is a form of structured learning that yields something new with value.

RB: What role does communication play in leadership and conflict?

LW: Conflict is an inevitable part of the human experience because it reflects the tension between the status quo and something else that’s trying to emerge. It can appear even in the process of solving daily problems, so the ability to deal productively with conflict, from simple misunderstandings to seemingly intractable differences, is crucial.

The source code for effective conflict engagement is effective conversations.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

The real challenge in leadership isn’t preventing conflict—it’s recognizing that conflict is already happening and choosing to engage with it productively through conversation

This conversation with Laura reminded me that innovation and change don’t just thrive on new ideas. They require leaders who are self-aware enough to listen, humble enough to ask for feedback, and courageous enough to stay in the tension long enough for something better to emerge.

5 Questions: Tendayi Viki on Building Innovation Momentum Without the Struggle

Innovation efforts get stuck long before they scale because innovation isn’t an idea problem. It’s a leadership problem. And one of those problems is that leaders are expected to spark transformation, without rocking the boat.

I’ve spent my career in corporate innovation (and wrote a book about it), so I was thrilled to sit down with Tendayi Viki, author of Pirates in the Navy and one of the most thoughtful voices on corporate innovation.

Our conversation didn’t follow the usual playbook about frameworks and metrics. Instead, it surfaced something deeper: how small wins, earned trust, and emotional intelligence quietly power real change.

If you’re tasked with driving innovation inside a large organization—or supporting the people who are—this conversation will challenge what you think it takes to succeed.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Robyn Bolton: You work with a lot of corporate leaders. What’s one piece of conventional wisdom they need to unlearn about innovation?

Tendayi Viki: That you need to start with a big bang. That transformation only works if it launches with maximum support and visibility from day one.

But we don’t think that way about launching new products. We talk about starting with early adopters. Steve Blank even outlines five traits of early evangelists: they know they have the problem, they care about solving it, they’re actively searching for a solution, they’ve tried to fix it themselves, and they have budget. That’s where momentum comes from.

But in corporate settings, I see leaders trying to roll out transformation as if it is a company-wide software update. I once worked with someone in South Africa who was introduced as the new head of innovation at a big all-hands event. He told me later, “I wish I hadn’t started with such a big bang. It created resentment—I hadn’t even built a track record yet.”

Instead of struggling and pushing change on people, I try to help leaders build momentum. Think of it like a flywheel. You start slow, with the right people, at the right points of leverage. You work with early adopter leaders, tell stories about their wins, invite others to join. Soon, you’re not persuading anyone—you’ve got movement.

RB: Have you seen that kind of momentum work in practice?

TV: A few great examples stand out.

Claudia Kotchka at P&G didn’t go around talking about design thinking when she started. She picked a struggling brand and applied the tools there. Once that project succeeded, people paid attention. More leaders asked for help. That success did the selling.

And there’s a story from Samsung that stuck with me. A transformation team was tasked with leading “big innovation,” but they didn’t start by preaching theory. They said, “Let’s help senior leaders solve the problems they’re dealing with right now.” Not future-state stuff—just practical challenges. They built credibility by delivering value, not running roadshows.

If you can’t find early adopters, then take one step back. Solve someone’s actual problem. People are always fans of solving their own problems.

RB: When you think about leaders who are good at building momentum, what qualities or mindsets do they tend to have?

TV: Patience is huge. This stuff takes time. And you have to set expectations with the people who gave you the mandate: “It’s not going to look like much at first—but it’s working.”

And I think you can measure momentum. Not just adoption metrics, but something simpler: how many people are coming to you without you pushing them? That’s real traction. You don’t have to chase them. They’re curious. They’ve seen the early wins.

Another big one is humility. You’ve got to respect the people who resist you. That doesn’t mean agreeing with them, but it means understanding. Maybe they need to see social proof. Maybe they’re waiting for cover from another leader. Maybe they’re not comfortable standing out.

None of that means they’re wrong. It just means they’re human. So work with the confident few first and bring in the rest when they’re ready.

RB: Have you always approached resistance that way?

TV: Oh no—I learned that one the hard way.

Early in my career, I was running a workshop at Pearson. I was beating up on this publishing group about how they’re going to get killed by digital, and they were arguing. It was a really difficult conversation, and I was convinced I was right and they were wrong.

Afterward, one of the leaders pulled me aside and said, “I don’t disagree with what you said. I think you’re right. But I didn’t like how you made us feel.”

And that was the moment. They weren’t resisting because of the content. They were reacting to how I delivered it. I made them feel stupid, even if I didn’t mean to. And their only move was to push back.

It took me years to absorb that lesson. But now I never forget: if people are resisting, check the emotional tone before you check the content.

RB: Last question. What is one thing you’d like to say to corporate leaders trying to drive innovation?

TV: Just chill!

Seriously. There’s so much *efforting* in corporate transformation. All the chasing, tracking, nudging, following up. “Have they responded to the email? Did you call them?” All that pressure to push, to prove.

But it reminds me of this Malcolm Gladwell podcast, Relax and Win, about San Jose State sprinters. Their coach taught them that to run their fastest, they had to stay relaxed. When you tense up, you actually slow down.

Innovation works the same way. Don’t force it. Build momentum. Let it grow. And trust it once it’s moving.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

The real challenge in corporate innovation isn’t convincing people that change is needed—it’s helping them feel safe enough to join you.

This conversation with Tendayi reminded me that the most effective innovation leaders don’t lead with pressure or pitch decks. They lead with patience, empathy, and small wins that build momentum.