Winning in Times of Uncertainty Requires Doing what 91% of Executives Won’t

In times of great uncertainty, we seek safety. But what does “safety” look like?

What we say: Safety = Data

We tend to believe that we are rational beings and, as a result, we rely on data to make decisions.

Great! We’ve got lots of data from lots of uncertain periods. HBR examined 4,700 public companies during three global recessions (1980, 1990, and 2000). They found that the companies that the companies that emerged “outperforming rivals in their industry by at least 10% in terms of sales and profits growth” had one thing in common: They aggressively made cuts to improve operational efficiency and ruthlessly invested in marketing, R&D, and building new assets to better serve customers have the highest probability of emerging as markets leaders post-recession.

This research was backed up in 2020 in a McKinsey study that found that “Organizations that maintained their innovation focus through the 2009 financial crisis, for example, emerged stronger, outperforming the market average by more than 30 percent and continuing to deliver accelerated growth over the subsequent three to five years.”

What we do: Safety = Hoarding

The reality is that we are human beings and, as a result, make decisions based on how we feel and the use data to justify those decisions.

How else do you explain that despite the data, only 9% of companies took the balanced approach recommended in the HBR study and, ten years later, only 25% of the companies studied by McKinsey stated that “capturing new growth” was a top priority coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Uncertainty is scary so, as individuals and as organizations, we scramble to secure scarce resources, cut anything that feels extraneous, and shift or focus to survival.

What now? And, not Or.

What was true in 2010 is still true today and new research from Bain offers practical advice for how leaders can follow both their hearts and their heads.

Implement systems to protect you from yourself. Bain studied Fast Company’s 50 Most Innovative Companies and found that 79% use two different operating models for innovation to combat executives’ natural risk aversion. The first, for sustaining innovation uses traditional stage-gate models, seeks input from experts and existing customers, and is evaluated on ROI-driven metrics.

The second, for breakthrough innovations, is designed to embrace and manage uncertainty by learning from new customers and emerging trends, working with speed and agility, engaging non-traditional collaborators, and evaluating projects based on their long-term potential and strategic option value.

Don’t outspend. Out-allocate. Supporting the two-system approach, nearly half of the companies studied send less on R&D than their peers overall and spend it differently: 39% of their R&D budgets to sustaining innovations and 61% to expanding into new categories or business models.

Use AI to accelerate, not create. Companies integrating AI into innovation processes have seen design-to-launch timelines shrink by 20% or more. The key word there is “integrate,” not outsource. They use AI for data and trend analysis, rapid prototyping, and automating repetitive tasks. But they still rely on humans for original thinking, intuition-based decisions, and genuine customer empathy.

Prioritize humans above all else. Even though all the information in the world is at our fingerprints, humans remain unknowable, unpredictable, and wonderfully weird. That’s why successful companies use AI to enhance, not replace, direct engagement with customers. They use synthetic personas as a rehearsal space for brainstorming, designing research, and concept testing. But they also know there is no replacement (yet) for human-to-human interaction, especially when creating new offerings and business models.

In times of great uncertainty, we seek safety. But safety doesn’t guarantee certainty. Nothing does. So, the safest thing we can do is learn from the past, prepare (not plan) for the future, make the best decisions possible based on what we know and feel today, and stay open to changing them tomorrow.

3 Signs Your AI Strategy Was Developed by the Underpants Gnomes

“It just popped up one day. Who knows how long they worked on it or how many of millions were spent. They told us to think of it as ChatGPT but trained on everything our company has ever done so we can ask it anything and get an answer immediately.”

The words my client was using to describe her company’s new AI Chatbot made it sound like a miracle. Her tone said something else completely.

“It sounds helpful,” I offered. “Have you tried it?”

“I’m not training my replacement! And I’m not going to train my R&D, Supply Chain, Customer Insights, or Finance colleagues’ replacements either. And I’m not alone. I don’t think anyone’s using it because the company just announced they’re tracking usage and, if we don’t use it daily, that will be reflected in our performance reviews.”

All I could do was sigh. The Underpants Gnomes have struck again.

Who are the Underpants Gnomes?

The Underpants Gnomes are the stars of a 1998 South Park episode described by media critic Paul Cantor as, “the most fully developed defense of capitalism ever produced.”

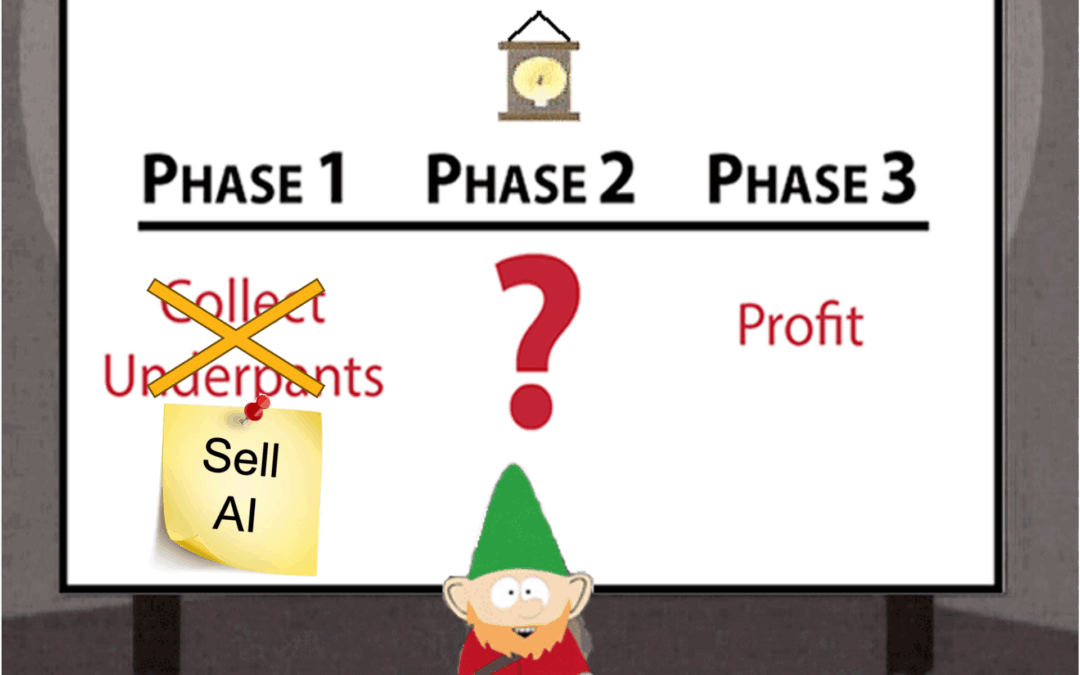

Claiming to be business experts, the Underpants Gnomes sneak into South Park residents’ homes every night and steal their underpants. When confronted by the boy in their underground lair, the Gnomes explain their business plan:

- Collect underpants

- ?

- Profit

It was meant as satire.

Some took it as a an abbreviated MBA.

How to Spot the Underpants AI Gnomes

As the AI hype grows, fueling executive FOMO (Fear of Missing Out), the Underpants Gnomes, cleverly disguised as experts, entrepreneurs and consultants, saw their opportunity.

- Sell AI

- ?

- Profit

While they’ve pivoted their business focus, they haven’t improved their operations so the Underpants AI Gnomes as still easy to spot:

- Investment without Intention: Is your company investing in AI because it’s “essential to future-proofing the business?” That sounds good but if your company can’t explain the future it’s proofing itself against and how AI builds a moat or a life preserver in that future, it’s a sign that the Gnomes are in the building.

- Switches, not Solutions: If your company thinks that AI adoption is as “easy as turning on Copilot” or “installing a custom GPT chatbot, the Gnomes are gaining traction. AI is a tool and you need to teach people how to use tools, build processes to support the change, and demonstrate the benefit.

- Activity without Achievement: When MIT published research indicating that 95% of corporate Gen AI pilots were failing, it was a sign of just how deeply the Gnomes have infiltrated companies. Experiments are essential at the start of any new venture but only useful if they generate replicable and scalable learning.

How to defend against the AI Gnomes

Odds are the gnomes are already in your company. But fear not, you can still turn “Phase 2:?” into something that actually leads to “Phase 3: Profit.”

- Start with the end in mind: Be specific about the outcome you are trying to achieve. The answer should be agnostic of AI and tied to business goals.

- Design with people at the center: Achieving your desired outcomes requires rethinking and redesigning existing processes. Strategic creativity like that requires combining people, processes, and technology to achieve and embed.

- Develop with discipline: Just because you can (run a pilot, sign up for a free trial), doesn’t mean you should. Small-scale experiments require the same degree of discipline as multi-million-dollar digital transformations. So, if you can’t articulate what you need to learn and how it contributes to the bigger goal, move on.

AI, in all its forms, is here to stay. But the same doesn’t have to be true for the AI Gnomes.

Have you spotted the Gnomes in your company?

The Top 5 Questions from 300 Innovators

“Is this what the dinosaurs did before the asteroid hit?”

That was the first question I was asked at IMPACT, InnoLead’s annual gathering of innovation practitioners, experts, and service providers.

It was also the first of many that provided insight into what’s on innovators and executives’ minds as we prepare for 2026

How can you prevent failure from being weaponized?

This is both a direct quote and a distressing insight into the state of corporate life. The era of “fail fast” is long gone and we’re even nostalgic for the days when we simply feared failure. Now, failure is now a weapon to be used against colleagues.

The answer is neither simple nor quick because it comes down to leadership and culture. Jit Kee Chin, Chief Technology Officer at Suffolk Construction, explained that Suffolk is able to stop the weaponization of failure because its Chairman goes to great lengths to role model a “no fault” culture within the company. “We always ask questions and have conversations before deciding on, judging, or acting on something,” she explained

How do you work with the Core Business to get things launched?

It’s long been innovation gospel that teams focused on anything other than incremental innovation must be separated, managerially and physically, from the core business to avoid being “infected” by the core’s unquestioning adherence to the status quo.

The reality, however, is the creation of Innovation Island, where ideas are created, incubated, and de-risked but remain stuck because they need to be accepted and adopted by the core business to scale.

The answer is as simple as it is effective: get input and feedback during concept development, find a core home and champion as your prototype, and work alongside them as you test and prepare to launch.

How do you organize for innovation?

For most companies, the residents of Innovation Island are a small group of functionally aligned people expected to usher innovations from their earliest stages all the way to launch and revenue-generation.

It may be time to rethink that.

Helen Riley, COO/CFO of Google X, shared that projects start with just one person working part-time until a prototype produces real-world learning. Tom Donaldson, Senior Vice President at the LEGO Group, explained that rather than one team with a large mandate, LEGO uses teams specially created for the type and phase of innovation being worked on.

What are you doing about sustainability?

Honestly, I was surprised by how frequently this question was asked. It could be because companies are combining innovation, sustainability, and other “non-essential” teams under a single umbrella to cut costs while continuing the work. Or it could be because sustainability has become a mandate for innovation teams.

I’m not sure of the reason and the answer is equally murky. While LEGO has been transparent about its sustainability goals and efforts, other speakers were more coy in their responses, for example citing the percentage of returned items that they refurbish or recycle but failing to mention the percentage of all products returned (i.e. 80% of a small number is still a small number).

How can humans thrive in an AI world?

“We’ll double down,” was Rana el Kaliouby’s answer. The co-founder and managing partner of Blue Tulip Ventures and host of Pioneers of AI podcast, showed no hesitation in her belief that humans will continue to thrive in the age of AI.

Citing her experience listening to Radiotopia Presents: Bot Love, she encouraged companies to set guardrails for how, when, and how long different AI services can be used. She also advocated for the need for companies to set metrics that go beyond measuring and maximizing usage time and engagement to considering the impact and value created by their AI-offerings.

What questions do you have?

The “Not So Obvious or Easy” Answer to Surviving the Next Decade

Last week, I shared that 74% of executives believe that their organizations will cease to exist in ten years. They believe that strategic transformation is required, but cite the obvious problem of organizational inertia and the easy scapegoat of people’s resistance to change.

Great. Now we know the problem. What’s the solution?

The Obvious: Put the Right People in Leadership Roles

Flipping through the report, the obvious answers (especially from an executive search firm) were front and center:

- Build a top team with relevant experience, competencies, and diverse backgrounds

- Develop the team and don’t be afraid to make changes along the way

- Set a common purpose and clear objectives, then actively manage the team

The Easy: Do Your Job as a Leader

OK, these may not be easy but it’s not that hard, either:

- Relentlessly and clearly communicate the why behind the change

- Change one thing at a time

- Align incentives to desired outcomes and behaviors

- Be a role model

- Understand and manage culture (remember, it’s reflected in the worst behaviors you tolerate)

The Not-Obvious-or-Easy-But-Still-Make-or-Break: Deputize the Next Generation

Buried amongst the obvious and easy was a rarely discussed, let alone implemented, choice – actively engaging the next generation of leaders.

But this isn’t the usual “invite a bunch of Hi-Pos (high potentials) to preview and upcoming announcement or participate in a focus group to share their opinions” performance most companies engage in.

This is something much different.

Step 1: Align on WHY an “extended leadership team” of Next Gen talent is mission critical

The C-Suite doesn’t see what happens on the front lines. It doesn’t know or understand the details of what’s working and what’s not. Instead, it receives information filtered through dozens of layers, all worried about positioning things just right.

Building a Next Gen extended leadership team puts the day-to-day realities front and center. It brings together capabilities that the C-Suite team may lack and creates the space for people to point out what looks good on paper but will be disastrous in practice.

Instead, leaders must commit to the purpose and value of engaging the next generation, not merely as “sensing mechanisms” (though that’s important, too) but as colleagues with different and equally valuable experiences and insights.

Step 2: Pick WHO is on the team without using the org chart

High-potentials are high potential because they know how to succeed in the current state. But transformation isn’t about replicating the current state. It requires creating a new state. For that, you need new perspectives:

- Super connecters who have wide, diverse, and trusted relationships across the organization so they can tap into a range of perspectives and connect the dots that most can barely see

- Credible experts who are trusted for their knowledge and experience and are known to be genuinely supportive of the changes being made

- Influencers who can rally the troops at the beginning and keep them motivated throughout

Step 3: Give them a clear mandate (WHAT) but don’t dictate HOW to fulfill it

During times of great change, it’s normal to want to control everything possible, including a team of brilliant, creative, and committed leaders. Don’t involve them in the following steps and be open to being surprised by their approaches and insights:

- At the beginning, involve them in understanding and defining the problem and opportunity.

- Throughout, engage them as advisors and influencers in decision-making (

- During and after implementation, empower them to continue to educate and motivate others and to make adaptations in real-time when needed.

Co-creation is the key to survival

Transforming your organization to survive, even thrive, in the future is hard work. Why not increase your odds of success by inviting the people who will inherit what you create to be part of the transformation?