by Robyn Bolton | Jan 25, 2026 | AI, Leadership, Leading Through Uncertainty

Spain, 1896

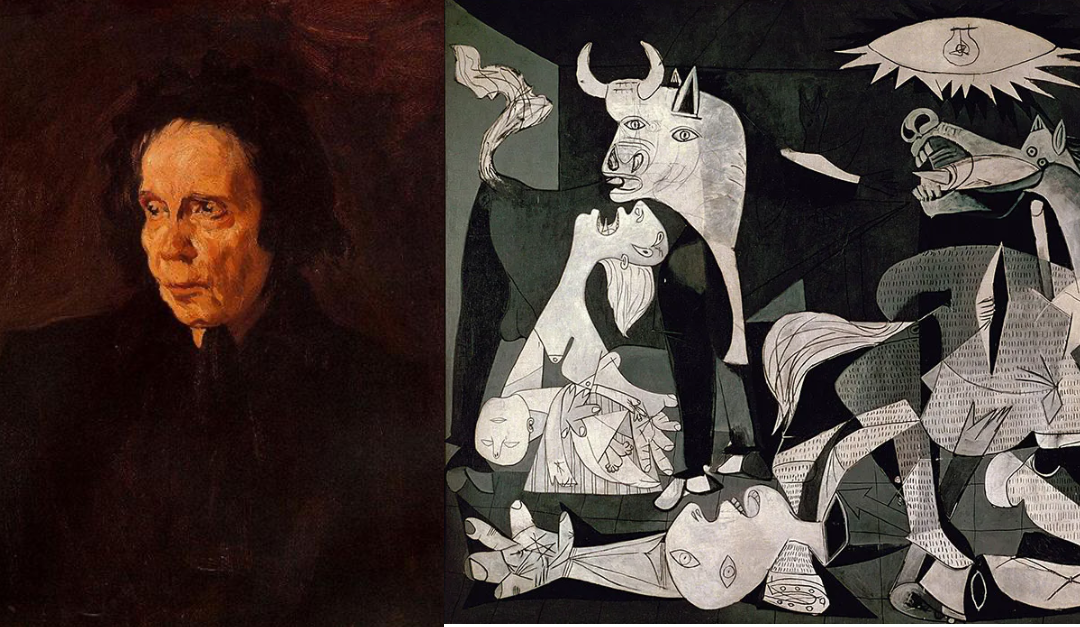

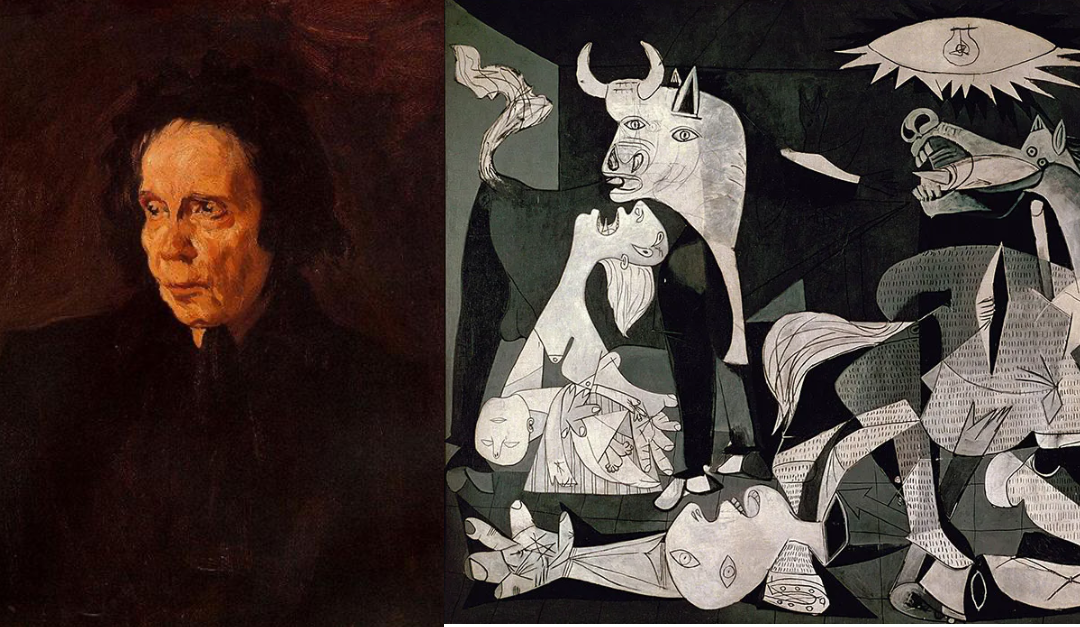

At the tender age of 14, Pablo Ruiz Picasso painted a portrait of his Aunt Pepa a work of brilliant academic realism that would go on to be hailed as “without a doubt one of the greatest in the whole history of Spanish painting.”

In 1901, he abandoned his mastery of realism, painting only in shades blue and blue-green.

There’s debate over why Picasso’s Blue Period began. Some argue that it’s a reflection of the poverty and desperation he experienced as a starving artist in Paris. Others claim it was a response to the suicide of his friend, Carles Casagemas. But Bill Gurley, a longtime venture capitalist, has a different theory.

Picasso abandoned realism because of the Kodak Brownie.

Introduced on February 1, 1900, the Kodak Brownie made photography widely available, fulfilling George Eastman’s promise that “you press the button, we do the rest.”

An ocean away, Gurley argues, Picasso’s “move toward abstraction wasn’t a rejection of skill; it was a recognition that realism had stopped being the frontier….So Picasso moved on, not because realism was wrong, but because it was finished.”

Washington DC, 2004

Three years before Drive took the world by storm, Daniel Pink published his third book, A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future.

In it, he argues that a combination of technological advancements, higher standards of living, and access to cheaper labor are pushing us from a world that values left brain skills like linear thought, analysis, and optimization towards one that requires right brain skills like artistry, empathy, and big picture thinking.

As a result, those who succeed in the future will be able to think like designers, tell stories with context and emotional impact, and combine disparate pieces into a whole greater than the sum of its parts. Leaders will need to be empathetic, able to create “a pathway to more intense creativity and inspiration,” and guide others in the pursuit of meaning and significance.

California, 2026

Barry O’Reilly, author of Unlearn, published his monthly blog post, “Six Counterintuitive Trends to Think about for 2026,” in which he outlines what he believes will be the human reactions to a world in which AI is everywhere.

Leadership, he asserts, will cease to be measured by the resources we control (and how well we control them to extract maximum value) but by judgment. Specifically, a leader’s ability to:

- Ask better questions

- Frame decisions clearly

- Hold ambiguity without freezing

- Know when not to use AI

The Price of Safety vs the Promise of Greatness

Picasso walked away from a thriving and lucrative market where he was an emerging star to suffer the poverty, uncertainty, and desperation of finding what was next. It would take more than a decade for him to find international acclaim. He would spend the rest of his life as the most famous and financially successful artist in the world.

Are you willing to take that same risk?

You can cling to the safety of what you know, the markets, industries, business models, structures, incentives that have always worked. You can continue to demand immediate efficiency, obedience, and profit while experimenting with new tech and playing with creative ideas.

Or you can start to build what’s next. You don’t have to abandon what works, just as Picasso didn’t abandon paint. But you do have to start using your resources in new ways. You must build the characteristics and capabilities that Daniel Pink outlines. You must become the “counterintuitive” leader that embraces ambiguity, role models critical thinking, and rewards creativity and risk-taking.

Do you have the courage to be counterintuitive?

Are you willing to embrace your inner Picasso?

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 17, 2026 | AI, Leadership, Leading Through Uncertainty, Stories & Examples

You’ve clarified the vision and strategy. Laid out the priorities and simplified the message. Held town halls, answered questions, and addressed concerns. Yet the AI initiative is stalled in ‘pilot mode,’ your team is focused solely on this quarter’s numbers, and real change feels impossible. You’re starting to suspect this isn’t a “change management” problem.

You’re right. It’s not.

The Data You’re Not Seeing

You’ve been doing what the research tells you to do: communicate clearly and frequently, clarify decision rights, and reduce change overload. And these things worked. Until employees went from grappling with two to 10 planned change initiatives in a single year. As the number went up, willingness to support organization change crashed, falling from 74% of employees in 2016 to 43% in 2022.

But here’s what the research isn’t telling you: despite your organizational fixes, your people are terrified. 77% of workers fear they’ll lose their jobs to AI in the next year. 70% fear they’ll be exposed as incompetent. And 66% of consumers, the highest level in a decade, expect unemployment to continue to rise.

Why doesn’t the research focus on fear? Because it’s uncomfortable. Messy. It’s a people (Behavior) problem, not a process (Architecture) problem and, as a result, you can’t fix it with a new org chart or better meeting cadence.

The organizational fixes are necessary. They’re just not sufficient to give people the psychological reassurance, resilience, and tools required to navigate an environment in which change is exponential, existential, and constant.

What Actually Works

In 2014, Microsoft was toxic and employees were afraid. Stack ranking meant every conversation was a competition, every mistake was career-limiting, and every decision was a chance to lose status. The company was dying not from bad strategy, but from fear.

CEO Satya Nadella didn’t follow the old change management playbook. He did more:

First, he eliminated the structures that created fear, including the stack ranking system, the zero-sum performance reviews, the incentives that punished mistakes. These were Architecture fixes, and they mattered.

And he addressed the messy, uncomfortable emotions that drove Behavior and Culture. He role modeled the Behaviors required to make it psychologically safe to be wrong. He introduced the “growth mindset” not as a poster on the wall, but as explicit permission to not have all the answers. When he made a public gaffe about gender equality, he immediately emailed all 200,000 employees: “My answer was very bad.” No spin. No excuses. Just modeling the vulnerability that he expected from everyone.

Ten years later, Microsoft is worth $2.5 trillion. Employee engagement and morale are dramatically improved because Nadella addressed the structures that fed fear AND the fear itself.

What This Means for You

You don’t need to be Satya Nadella. But you do need to stop pretending fear doesn’t exist in your organization.

Name it early and often. Not just in the all-hands meeting, but in the team meetings and lunch-and-learns. Be honest, “Some roles will change with this AI implementation. Here’s what we know and don’t know.” Make the implicit explicit.

Eliminate the structures that create fear. If your performance system pits people against each other, change it. If people get punished for taking smart risks, stop. If people ask questions or make suggestions, listen and act.

Be vulnerable. Share what you’re uncertain about. Admit when you don’t know. Show that it’s safe to be learning. Demonstrate that learning is better than (pretending to) know.

The stakes aren’t abstract: That AI pilot stuck in testing. The strategic initiative that gets compliance but not commitment. The team so focused on surviving today they can’t prepare for tomorrow. These aren’t communication failures. They’re misaligned ABCs that allow fear to masquerade as pragmatism.

And the masquerade only stops when you align align the ABCs all at once. Because fixing Architecture without changing your Behavior simply gives fear a new place to hide.

by Robyn Bolton | Jan 11, 2026 | Leading Through Uncertainty, Strategy

We’re two full weeks into the new year and I’m curious, how is the strategy and operating plan you spent all Q3 and Q4 working on progressing? You nailed it, right? Everything is just as you expected and things are moving forward just as you planned.

I didn’t think so.

So, like many others, you feel tempted to double down on what worked before or chase every opportunity with the hope that it will “future-proof” your business.

Stop.

Remember the Cheshire Cat, “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there.”

You DO know where you’re going because your goals didn’t change. You still need to grow revenue and cut costs with fewer resources than last year.

The map changed. So you need to find a new road.

You’re not going to find it by looking at old playbooks or by following every path available.

You will find it by following these three steps (and don’t require months or millions to complete).

Return to First Principles

When old maps fail and new roads are uncertain, the most successful leaders return to first principles, the fundamental, irreducible truths of a subject:

- Organizations are systems

- Systems seek equilibrium and resist change when elements are misaligned

- People in the system do what the system allows, models, and rewards

Returning to these principles is the root of success because it forces you to pause and ask the right questions before (re)acting.

Ask Questions to Find the Root Cause

Based on the first principles, think of your organization as a lock. All the tumblers need to align to unlock the organization’s potential to get to where you need to go. When the tumblers don’t align, you stay stuck in the dying status quo.

Every organization has three tumblers – Architecture (how you’re organized), Behavior (what leaders actually do), and Culture (what gets rewarded) – that must align to develop and execute a strategy in an environment of uncertainty and constant change.

But ensuring that you’ve aligned all three tumblers, and not just one or two, requires asking questions to get to the root cause of the challenges.

Is your leadership team struggling to align on a decision because they don’t have enough data or can’t agree on what it means? The Behavior and Culture tumblers are misaligned with the structure and incentives of Architecture

Are people resisting the new AI tools you rolled out? Architectural incentives and metrics, and leadership communications and behaviors are preventing buy-in.

Struggling to squeeze growth out of a stagnant business? Structures and systems combined with organization culture are reinforcing safety and a fixed mindset rather than encouraging curiosity and learning.

Align the Tumblers

When you diagnose the root causes you find the misaligned tumbler. And, in the process of bringing it into alignment, it will likely pull the others in, too.

By role modeling leadership behaviors that encourage transparent communication (no hiding behind buzzwords), quantifying confidence, and smart risk taking, you’ll also influence culture and may reveal a needed change in Architecture.

Modifying the metrics and rewards in Architecture and making sure that your communications and behavior encourage buy-in to new AI tools, will start to establish an AI-friendly culture.

Overhauling Architecture to encourage and reward actions that expand that stagnant business into new markets or brings new solutions to your existing customers, will build new leadership Behaviors will drive culture change.

Get to your Goals

It’s a VUCA/BANI world AND It’s only going to accelerate. That means that the strategy you developed last quarter and the operational plans you set last month will be obsolete by the end of the week.

But the strategy and the plan were never the goal. They were the road you planned based on the map you had. When the map changes, the road does, too. But you can still get to the goal if you’re willing to fiddle with a lock.

by Robyn Bolton | Dec 10, 2025 | Customer Centricity, Innovation, Leading Through Uncertainty

In times of great uncertainty, we seek safety. But what does “safety” look like?

What we say: Safety = Data

We tend to believe that we are rational beings and, as a result, we rely on data to make decisions.

Great! We’ve got lots of data from lots of uncertain periods. HBR examined 4,700 public companies during three global recessions (1980, 1990, and 2000). They found that the companies that the companies that emerged “outperforming rivals in their industry by at least 10% in terms of sales and profits growth” had one thing in common: They aggressively made cuts to improve operational efficiency and ruthlessly invested in marketing, R&D, and building new assets to better serve customers have the highest probability of emerging as markets leaders post-recession.

This research was backed up in 2020 in a McKinsey study that found that “Organizations that maintained their innovation focus through the 2009 financial crisis, for example, emerged stronger, outperforming the market average by more than 30 percent and continuing to deliver accelerated growth over the subsequent three to five years.”

What we do: Safety = Hoarding

The reality is that we are human beings and, as a result, make decisions based on how we feel and the use data to justify those decisions.

How else do you explain that despite the data, only 9% of companies took the balanced approach recommended in the HBR study and, ten years later, only 25% of the companies studied by McKinsey stated that “capturing new growth” was a top priority coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Uncertainty is scary so, as individuals and as organizations, we scramble to secure scarce resources, cut anything that feels extraneous, and shift or focus to survival.

What now? And, not Or.

What was true in 2010 is still true today and new research from Bain offers practical advice for how leaders can follow both their hearts and their heads.

Implement systems to protect you from yourself. Bain studied Fast Company’s 50 Most Innovative Companies and found that 79% use two different operating models for innovation to combat executives’ natural risk aversion. The first, for sustaining innovation uses traditional stage-gate models, seeks input from experts and existing customers, and is evaluated on ROI-driven metrics.

The second, for breakthrough innovations, is designed to embrace and manage uncertainty by learning from new customers and emerging trends, working with speed and agility, engaging non-traditional collaborators, and evaluating projects based on their long-term potential and strategic option value.

Don’t outspend. Out-allocate. Supporting the two-system approach, nearly half of the companies studied send less on R&D than their peers overall and spend it differently: 39% of their R&D budgets to sustaining innovations and 61% to expanding into new categories or business models.

Use AI to accelerate, not create. Companies integrating AI into innovation processes have seen design-to-launch timelines shrink by 20% or more. The key word there is “integrate,” not outsource. They use AI for data and trend analysis, rapid prototyping, and automating repetitive tasks. But they still rely on humans for original thinking, intuition-based decisions, and genuine customer empathy.

Prioritize humans above all else. Even though all the information in the world is at our fingerprints, humans remain unknowable, unpredictable, and wonderfully weird. That’s why successful companies use AI to enhance, not replace, direct engagement with customers. They use synthetic personas as a rehearsal space for brainstorming, designing research, and concept testing. But they also know there is no replacement (yet) for human-to-human interaction, especially when creating new offerings and business models.

In times of great uncertainty, we seek safety. But safety doesn’t guarantee certainty. Nothing does. So, the safest thing we can do is learn from the past, prepare (not plan) for the future, make the best decisions possible based on what we know and feel today, and stay open to changing them tomorrow.

by Robyn Bolton | Nov 11, 2025 | Leadership, Leading Through Uncertainty

The business press has a new obsession with courageous leadership.

Harvard Business Review dedicated their September cover story to it. Nordic Business Forum built an entire 2024 conference around it. BetterUp, McKinsey, and dozens of thought leaders and influencers can’t stop talking about it.

Here’s what they’re all telling you: If you’re playing it safe, stuck in analysis paralysis, not innovating fast enough, or not making bold moves, then you are the problem because you lack courage.

Here’s what they’re not telling you: You don’t have a courage problem. You have a systems problem.

The Real Story Behind “Courage Gaps”

The VP was anything but cowardly. She had a track record of bold moves and wasn’t afraid of hard conversations. The CEO wanted to transform the company by moving from a product-only focus to one offering holistic solutions that combined hardware, software, and services. This VP was the obvious choice.

Her team came to her with a ideas that would reposition the company for long-term growth. She loved it. They tested the ideas. Customers loved them. But not a single one ever launched.

It wasn’t because the VP or the CEO lacked courage. It was because the board measured success in annual improvements, the CEO’s compensation structure rewarded short-term performance, and the VP required sign-off from six different stakeholders who were evaluated on risk mitigation. At every level, the system was designed to kill bold ideas. And it worked.

This is the inconvenient truth the courage press ignores.

That success doesn’t just require leaders who are courageous, it requires organizational architecture that systematically rewards courage and manages risk.

What We’re Really Asking Leaders to Overcome

Consider what we’re actually asking leaders to be courageous against:

- Compensation structures tied to short-term metrics

- Risk management processes designed to say “no”

- Approval hierarchies where one skeptic can overrule ten enthusiasts

- Cultures where failed experiments end careers

The courage discourse lets broken systems off the hook.

It’s easier to sell “10 Ways to Build Leadership Courage” than to admit that organizational incentives, governance structures, and cultural norms are actively working against the bold moves we tell leaders to make.

What Actually Enables Courageous Leadership.

I’m not arguing that there isn’t a need for individual courage. There is.

But telling someone to “be braver” when their organizational architecture punishes bravery is like telling someone to swim faster in a pool filled with Jell-O.

If we want courage, we need to fix the things the systems that discourage it:

- Align incentives with the time horizon of the decisions you want made

- Create explicit permission structures for experimentation

- Build decision-making processes that don’t require unanimous consent

- Separate “learning investments” from “performance expectations” when measuring results

- Make the criteria for bold moves clear, not subject to whoever’s in the room

But doing this is a lot harder than buying books about courage.

The Bottom Line

When you fix the architecture, you don’t need to constantly remind people to be brave because the system enables. Individual courage becomes the expectation, not the exception.

The real question isn’t whether your leaders need courage.

It’s whether your organization has the architecture to let them use it.

If you can’t answer that question, that’s not a courage problem.

That’s a design problem.

And design is something that, as a leader, you can actually control.

by Robyn Bolton | Nov 1, 2025 | Innovation, Leading Through Uncertainty

“Is this what the dinosaurs did before the asteroid hit?”

That was the first question I was asked at IMPACT, InnoLead’s annual gathering of innovation practitioners, experts, and service providers.

It was also the first of many that provided insight into what’s on innovators and executives’ minds as we prepare for 2026

How can you prevent failure from being weaponized?

This is both a direct quote and a distressing insight into the state of corporate life. The era of “fail fast” is long gone and we’re even nostalgic for the days when we simply feared failure. Now, failure is now a weapon to be used against colleagues.

The answer is neither simple nor quick because it comes down to leadership and culture. Jit Kee Chin, Chief Technology Officer at Suffolk Construction, explained that Suffolk is able to stop the weaponization of failure because its Chairman goes to great lengths to role model a “no fault” culture within the company. “We always ask questions and have conversations before deciding on, judging, or acting on something,” she explained

How do you work with the Core Business to get things launched?

It’s long been innovation gospel that teams focused on anything other than incremental innovation must be separated, managerially and physically, from the core business to avoid being “infected” by the core’s unquestioning adherence to the status quo.

The reality, however, is the creation of Innovation Island, where ideas are created, incubated, and de-risked but remain stuck because they need to be accepted and adopted by the core business to scale.

The answer is as simple as it is effective: get input and feedback during concept development, find a core home and champion as your prototype, and work alongside them as you test and prepare to launch.

How do you organize for innovation?

For most companies, the residents of Innovation Island are a small group of functionally aligned people expected to usher innovations from their earliest stages all the way to launch and revenue-generation.

It may be time to rethink that.

Helen Riley, COO/CFO of Google X, shared that projects start with just one person working part-time until a prototype produces real-world learning. Tom Donaldson, Senior Vice President at the LEGO Group, explained that rather than one team with a large mandate, LEGO uses teams specially created for the type and phase of innovation being worked on.

What are you doing about sustainability?

Honestly, I was surprised by how frequently this question was asked. It could be because companies are combining innovation, sustainability, and other “non-essential” teams under a single umbrella to cut costs while continuing the work. Or it could be because sustainability has become a mandate for innovation teams.

I’m not sure of the reason and the answer is equally murky. While LEGO has been transparent about its sustainability goals and efforts, other speakers were more coy in their responses, for example citing the percentage of returned items that they refurbish or recycle but failing to mention the percentage of all products returned (i.e. 80% of a small number is still a small number).

How can humans thrive in an AI world?

“We’ll double down,” was Rana el Kaliouby’s answer. The co-founder and managing partner of Blue Tulip Ventures and host of Pioneers of AI podcast, showed no hesitation in her belief that humans will continue to thrive in the age of AI.

Citing her experience listening to Radiotopia Presents: Bot Love, she encouraged companies to set guardrails for how, when, and how long different AI services can be used. She also advocated for the need for companies to set metrics that go beyond measuring and maximizing usage time and engagement to considering the impact and value created by their AI-offerings.

What questions do you have?