by Robyn Bolton | May 21, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

“What will you do on vacation?” a colleague asked.

“Nothing,” I replied.

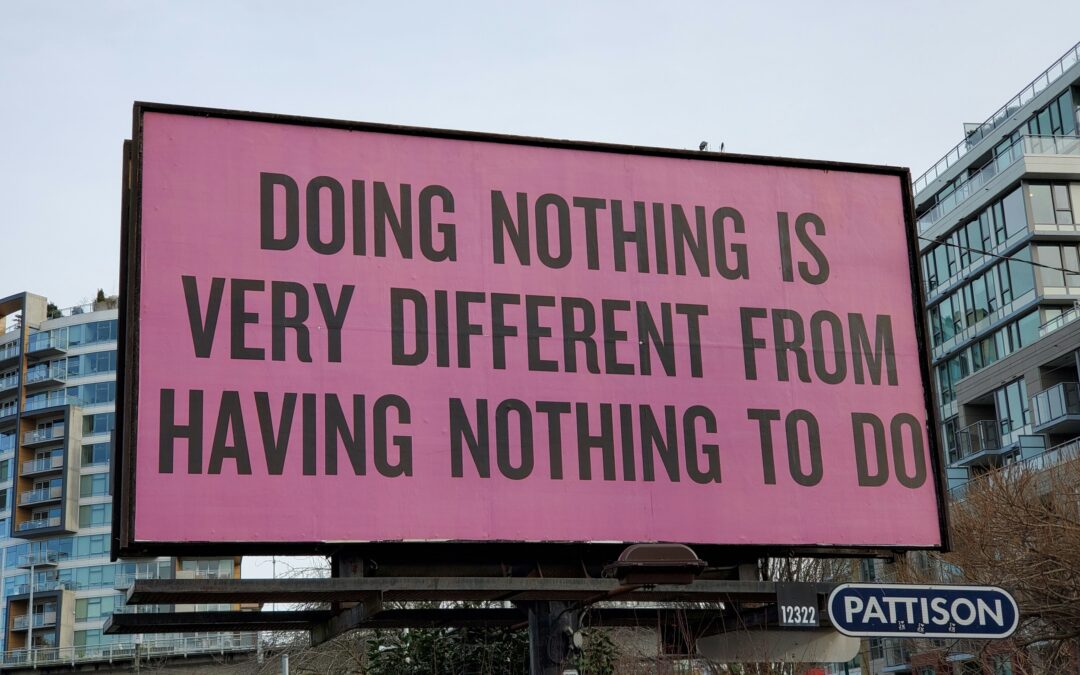

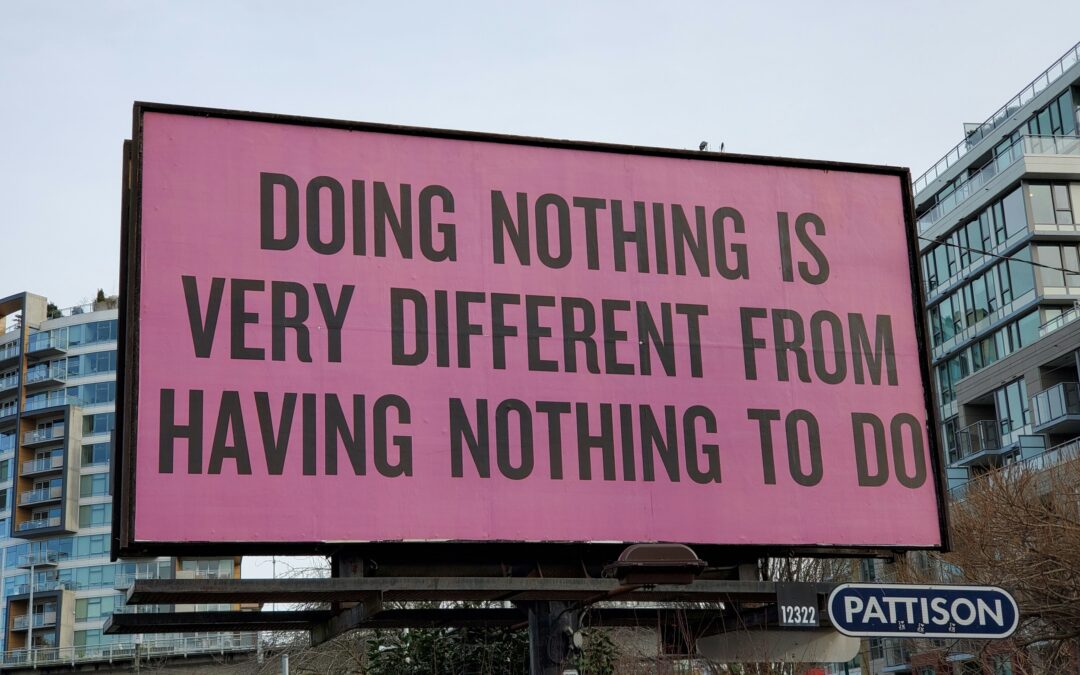

The uncomfortable silence that followed spoke volumes. In boardrooms and during quarterly reviews, we celebrate constant motion and back-to-back calendars. Yet, study after study shows that the most successful leaders embrace a counterintuitive edge: strategic idleness.

While your competitors exhaust themselves in perpetual busyness, research shows that deliberate mental downtime activates the brain networks responsible for strategic foresight, innovative solutions, and clear decision-making.

The Status Trap of Busy-ness

At one company I worked with, there was only one acceptable answer to “How are you doing?” “Busy.” The answer wasn’t a way to avoid an awkward hallway conversation. It was social currency. If you’re busy, you’re valuable. If you’re fine, you’re expendable.

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Consumer Research confirmed what Columbia, Georgetown, and Harvard researchers discovered: being busy is now a status symbol, signaling “competence, ambition, and scarcity in the market.”

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: your packed schedule is undermining the very outcomes you’re accountable for delivering.

Your Brain’s Innovation Engine

Neuroscience has confirmed what innovators have long practiced: Strategic Idleness. While you consciously “do nothing,” your default mode network (DMN) engages, making unexpected connections across stored information and experiences.

Recent research published in the journal Brain demonstrates that the DMN is activated during creative thinking, with a specific pattern of neural activity occurring during the search for novel ideas. This network is essential for both spontaneous thought and divergent thinking, core elements of innovation.

So if you’ve always wondered why you get your best ideas in the shower, it’s because your DMN is powered all the way up.

Three Ways to Power-Up Your Engine

Here are three executive-grade approaches to strategic idleness without more showers or productivity sacrifices:

- Pause for 10 Minutes Before Making a Decision

Before making high-stakes decisions, implement a mandatory 10-minute idleness period. No email, no conversation—just sitting. Research on cognitive recovery suggests that this brief reset activates your DMN, allowing for a more comprehensive consideration of variables and strategic implications.

- Take a Walking Meeting with Yourself

Block 20 minutes in your calendar each week for a solo walking meeting (and then take the walk!). No other attendees, no agenda, just walking. Researchers at Stanford University found that walking increases creative output by an average of 60% compared to sitting. The combination of physical movement and mental space creates ideal conditions for your brain to generate solutions to problems you didn’t know you had.

- Schedule 3-5 minutes of Strategic Silence before key discussions

Research on group dynamics shows that silent reflection before discussion can reduce groupthink and increase the quality of ideas by helping team members process information more deeply. Before you dive into a critical topic at your next leadership meeting, schedule 3-5 minutes of silence. Explain that this silence is for individual reflection and planning for the upcoming discussion, not for checking email or taking bathroom breaks. Acknowledge that it will feel awkward, but that it’s critical for the upcoming discussion and decision.

Remember, You’re Not Doing Nothing If You’re being Strategically Idle

The most valuable asset in your organization isn’t technology, capital, or even the products you sell. It’s the quality of thinking that goes into critical decisions. Strategic idleness isn’t inaction; it’s the deliberate cultivation of conditions that foster innovation, clear judgment, and strategic foresight.

While your competitors remain trapped in perpetual busyness, by using executive advantage of strategic idleness, your next breakthrough will present itself.

This is an updated version of the June 9, 2019, post, “Do More Nothing.”

by Robyn Bolton | May 10, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership

You need friction to create fire. It’s true whether you’re camping or leading change inside an organization. Yet most of us avoid conflict—we ignore it, smooth it over, or sideline the people who spark it.

I’ve been guilty of that too, which is why I was eager to sit down with Laura Weiss, founder of Design Diplomacy, former architect and IDEO partner, university educator, and professional mediator, to explore why conflict isn’t the enemy of innovation, but one of its essential ingredients.

Our conversation wasn’t about frameworks or facilitation tricks. It was about something deeper: how leaders can unlearn their fear of conflict, lean into discomfort, and use it to build trust, fuel learning, and drive meaningful change.

So if conflict feels like a threat to alignment and progress, this conversation will show you why embracing it is the real leadership move.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Robyn Bolton: What’s the one piece of conventional wisdom about change that organizations need to unlearn?

Laura Weiss: The belief that change is event-driven. It’s not, except for seismic shifts like the Great Recession, the COVID-19 pandemic, 9/11, and October 7. It’s happening all the time! As a result, leading change should be seen as a continuous endeavor that prepares the organization to be agile when unforeseen events occur.

RB: Wow, that is capital-T True! What is driving this misperception?

LW: It’s been said that ‘managers deal with complexity, but leaders deal with change’. So, it all comes down to leadership. However, the prevailing belief is that a “leader” is the person who has risen to the top of the organization and has all the answers.

In many design professions, those who are promoted to leadership roles are exceptional at their craft. But evolving from an ‘individual contributor’ to leading others involves skills that can seem contrary to our beliefs about leadership. One is humility – the capability to say “I don’t know” without feeling exposed as a fraud, especially in professions where being a “subject matter expert” is expected. Being humble presents the leader as human, which leads to another skill: connecting with others as humans before attempting to ‘lead’ them. I particularly like Edgar Schein’s relationship-driven leadership philosophy as opposed to ‘transactional’ leadership, where your role relative to others dictates how you interact.

RB: From your experience, how can we unlearn this and lead differently?

LW: Leaders need to do three things:

- Be self-aware. After becoming a certified coach, it became clear to me that all leadership begins with understanding oneself. If you’re unaware of how you operate in the world, you certainly can’t lead others effectively.

- Be agile. Machiavelli famously asked: “Is it better to be loved or feared…?” Being a leader requires the ability to do both, operating along the ‘warmth-strength’ continuum, starting with warmth. There are six leadership styles a leader should be familiar with, in the same way that golfers know which golf club to use for a particular situation.

- Evolve. This means feedback – being willing to ask for it and receive it. Many senior leaders stop receiving feedback as they progress in their careers. But times change, and ‘what got you here won’t get you there.’ Holding up a mirror to very senior leaders who have rarely, if ever, received feedback, or have received it but didn’t really “get it,” is critical if they are to change with the times and the needs of their organization.

RB: Amen! I’m starting to sense a connection between leadership, innovation, and change, but before I make assumptions, what do you see?

LW: First, I want to acknowledge the thesis of your book that “innovation isn’t an idea problem, it’s a leadership problem” – 1000% agree with that!

One of the reasons I shifted from being an architect to focusing on the broader world of innovation was that I was curious about why some innovation initiatives were successful and some were not. Specifically, I was curious about the role of conflict in the creative problem-solving process because conflict is critical to bringing innovation and change to life. Yet, it’s not something most of us are naturally good at – in fact, our brain is designed to avoid it!

The biggest myth about conflict is that it erodes trust and undermines relationships. The opposite is true – when handled well, productive conflict strengthens relationships and leads to better outcomes for organizations navigating change.

Just as with innovation, the organizations that are most successful with change are the ones that consistently use productive conflict as an enabler of change.

To achieve this, organizations must shift from a reactive stance to a proactive one and become more “discovery-driven”. This means practicing iterative prototyping and learning their way forward. In my mind, innovation is a form of structured learning that yields something new with value.

RB: What role does communication play in leadership and conflict?

LW: Conflict is an inevitable part of the human experience because it reflects the tension between the status quo and something else that’s trying to emerge. It can appear even in the process of solving daily problems, so the ability to deal productively with conflict, from simple misunderstandings to seemingly intractable differences, is crucial.

The source code for effective conflict engagement is effective conversations.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

The real challenge in leadership isn’t preventing conflict—it’s recognizing that conflict is already happening and choosing to engage with it productively through conversation

This conversation with Laura reminded me that innovation and change don’t just thrive on new ideas. They require leaders who are self-aware enough to listen, humble enough to ask for feedback, and courageous enough to stay in the tension long enough for something better to emerge.

by Robyn Bolton | Apr 21, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership

Innovation efforts get stuck long before they scale because innovation isn’t an idea problem. It’s a leadership problem. And one of those problems is that leaders are expected to spark transformation, without rocking the boat.

I’ve spent my career in corporate innovation (and wrote a book about it), so I was thrilled to sit down with Tendayi Viki, author of Pirates in the Navy and one of the most thoughtful voices on corporate innovation.

Our conversation didn’t follow the usual playbook about frameworks and metrics. Instead, it surfaced something deeper: how small wins, earned trust, and emotional intelligence quietly power real change.

If you’re tasked with driving innovation inside a large organization—or supporting the people who are—this conversation will challenge what you think it takes to succeed.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Robyn Bolton: You work with a lot of corporate leaders. What’s one piece of conventional wisdom they need to unlearn about innovation?

Tendayi Viki: That you need to start with a big bang. That transformation only works if it launches with maximum support and visibility from day one.

But we don’t think that way about launching new products. We talk about starting with early adopters. Steve Blank even outlines five traits of early evangelists: they know they have the problem, they care about solving it, they’re actively searching for a solution, they’ve tried to fix it themselves, and they have budget. That’s where momentum comes from.

But in corporate settings, I see leaders trying to roll out transformation as if it is a company-wide software update. I once worked with someone in South Africa who was introduced as the new head of innovation at a big all-hands event. He told me later, “I wish I hadn’t started with such a big bang. It created resentment—I hadn’t even built a track record yet.”

Instead of struggling and pushing change on people, I try to help leaders build momentum. Think of it like a flywheel. You start slow, with the right people, at the right points of leverage. You work with early adopter leaders, tell stories about their wins, invite others to join. Soon, you’re not persuading anyone—you’ve got movement.

RB: Have you seen that kind of momentum work in practice?

TV: A few great examples stand out.

Claudia Kotchka at P&G didn’t go around talking about design thinking when she started. She picked a struggling brand and applied the tools there. Once that project succeeded, people paid attention. More leaders asked for help. That success did the selling.

And there’s a story from Samsung that stuck with me. A transformation team was tasked with leading “big innovation,” but they didn’t start by preaching theory. They said, “Let’s help senior leaders solve the problems they’re dealing with right now.” Not future-state stuff—just practical challenges. They built credibility by delivering value, not running roadshows.

If you can’t find early adopters, then take one step back. Solve someone’s actual problem. People are always fans of solving their own problems.

RB: When you think about leaders who are good at building momentum, what qualities or mindsets do they tend to have?

TV: Patience is huge. This stuff takes time. And you have to set expectations with the people who gave you the mandate: “It’s not going to look like much at first—but it’s working.”

And I think you can measure momentum. Not just adoption metrics, but something simpler: how many people are coming to you without you pushing them? That’s real traction. You don’t have to chase them. They’re curious. They’ve seen the early wins.

Another big one is humility. You’ve got to respect the people who resist you. That doesn’t mean agreeing with them, but it means understanding. Maybe they need to see social proof. Maybe they’re waiting for cover from another leader. Maybe they’re not comfortable standing out.

None of that means they’re wrong. It just means they’re human. So work with the confident few first and bring in the rest when they’re ready.

RB: Have you always approached resistance that way?

TV: Oh no—I learned that one the hard way.

Early in my career, I was running a workshop at Pearson. I was beating up on this publishing group about how they’re going to get killed by digital, and they were arguing. It was a really difficult conversation, and I was convinced I was right and they were wrong.

Afterward, one of the leaders pulled me aside and said, “I don’t disagree with what you said. I think you’re right. But I didn’t like how you made us feel.”

And that was the moment. They weren’t resisting because of the content. They were reacting to how I delivered it. I made them feel stupid, even if I didn’t mean to. And their only move was to push back.

It took me years to absorb that lesson. But now I never forget: if people are resisting, check the emotional tone before you check the content.

RB: Last question. What is one thing you’d like to say to corporate leaders trying to drive innovation?

TV: Just chill!

Seriously. There’s so much *efforting* in corporate transformation. All the chasing, tracking, nudging, following up. “Have they responded to the email? Did you call them?” All that pressure to push, to prove.

But it reminds me of this Malcolm Gladwell podcast, Relax and Win, about San Jose State sprinters. Their coach taught them that to run their fastest, they had to stay relaxed. When you tense up, you actually slow down.

Innovation works the same way. Don’t force it. Build momentum. Let it grow. And trust it once it’s moving.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

The real challenge in corporate innovation isn’t convincing people that change is needed—it’s helping them feel safe enough to join you.

This conversation with Tendayi reminded me that the most effective innovation leaders don’t lead with pressure or pitch decks. They lead with patience, empathy, and small wins that build momentum.

by Robyn Bolton | Apr 15, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership

“The call is coming from inside the house” is one of those classic quotes that crossed over from urban legend and horror movies to become a common pop-culture phrase. While originally a warning to teenage babysitters, recent research indicates that it’s also a warning to corporate execs that murderous business threats are closer than they think.

In the early weeks of 2025, Box of Crayons, a Toronto-based learning and development company, partnered with The Harris Poll to survey over 1500 business leaders and knowledge workers to diagnose and understand the greatest challenges facing organizations.

They found that “while there is a tendency to focus on external pressures like economic uncertainty, technological disruptions, and labor market issues, our research shows the most critical challenges are unfolding within the workplace itself.”

The threat is coming from inside your house.

Here’s what they found and what you can do about it

Nearly 1 day each workweek “is lost to the fear of making mistakes.”

Fear is at the core of all the issues making headlines – burnout, disengagement, lost productivity. It “breeds doubt, prompting individuals to question themselves and others, instigating anxiety, hindering productivity, and promoting blame instead of teamwork.”

Fear is also a virus, spreading rapidly from one person to their team members and on and on until it infects the entire organization, embedding itself in the culture.

Executives and managers are key to breaking the cycle of fear that kills innovation, initiative, and growth. By reframing mistakes and learnings, rewarding smart risks even if they result in unexpected outcomes, and role-modeling behaviors that encourage trust and psychological safety, their daily and consistent actions can encourage bravery and remaking the culture.

70% of people don’t see value in listening to people they disagree with.

Unless you’re employed by Lumon Industries, it’s impossible to be a completely different person at work compared to who you are outside of work. So, it should come as no surprise that most people no longer listen to opinions, perspectives, or evidence with which they disagree.

The problem is that different perspectives and experiences are essential to elements of the problem-solving process. Without them, we cannot learn, develop new solutions, and innovate.

Again, executives and managers play a critical role in helping to surface diverse points of view and helping employees to engage in “productive conflict.” Rather than rushing to “consensus” or rapidly making a decision, by expressing curiosity and asking questions, people-leaders create space for new points of view and role model how to encourage and use it.

87% of leaders lack the skills needed to adapt. 64% say funding to build those skills has been cut.

Business leaders are fully aware of the changes happening within their teams, organizations, and the broader world. They recognize the need to constantly adapt, learn, and develop the skills required to respond to these changes. They can even articulate what they need help with, why, and how it will benefit the team or organization.

But leadership training is often one of the first items to be cut, leaving new and experienced people-leaders “ill-equipped to manage the increasing complexity of today’s workplace, stifling their ability to inspire, guide, and support their teams effectively.”

The solution is simple – invest in people. Given the acute need for support and training, forget big programs, multi-day offsites, and centralized learning agendas. Talk to the people asking for help to understand what they want and need and how they learn best. Share what you can do right now with the resources you have and engage them in creating a plan that helps them within the constraints of the current context.

Answer the phone

Just like that terrifying movie moment, the call threatening your business isn’t coming from mysterious outside forces—it’s echoing through your own hallways. The good news? Unlike those helpless babysitters in horror films, you can change the ending by confronting these internal threats head-on.

What internal “call” is your organization ignoring that deserves immediate attention?

by Robyn Bolton | Apr 9, 2025 | Innovation, Leadership, Tips, Tricks, & Tools

“A Few Good Men” is one of my favorite movies. As much as I love Jack Nicholson’s classic line, “You can’t handle the truth!” lately, I’ve been thinking more about a line delivered by Lt. Daniel Kaffee, played by Tom Cruise – “And the hits just keep on comin’.”

But, just like Lt. Kaffee had to make peace with Lt. Cdr JoAnne Galloway joining his Cuba trip, we must make peace with uncertainty and find the guts to move forward.

This is much easier said than done, but these three steps make it possible. Even profitable.

Where We Begin

Imagine you’re the CEO of Midwest Precision Components (MPW), a $75 million manufacturer of specialized valves and fittings. Forty percent of your components come from suppliers now subject to new tariffs, which, if they stay in effect, threaten an increase of 15% in material costs. This increase would devastate your margins and could require you to reduce staff.

Your competitors are scrambling to replace foreign suppliers with domestic ones. But you know that such rapid changes are also risky since higher domestic prices eat into your margins (though hopefully less than 15%), and insufficient time to quality test new parts could lead to product issues and lost customers. And all this activity assumes that the tariffs stay in place and aren’t suddenly paused or withdrawn.

3 Steps Forward

Entering the boardroom, you notice that the CFO looks more nervous than usual, and your head of Supply Chain is fighting a losing battle with a giant stack of catalogs. Taking a deep breath, you resolve to be creative, not reactive (same letters, different outcomes), and get to work.

Step 1: Start with the goal and work backward. The goal isn’t changing suppliers to reduce tariff impact. It’s maintaining profit margins without reducing headcount or product quality. With your CFO, you whiteboard a Reverse Income Statement, a tool that starts with required (not desired) profits to calculate necessary revenues and allowable costs. After running several scenarios, you land on believable assumptions that result in no more than a 4% increase in costs.

Step 2: Identify and prioritize assumptions. With the financial assumptions identified, you ask the leadership team to list everything that must be true to deliver the financial assumptions, their confidence that each of their assumptions is true, and the impact on the business and its bottom line if the assumption is wrong.

Knowing that your head of Sales is an unrelenting optimist and your Supply Chain head is mired in a world of doom and gloom, you set a standard scale: High confidence means betting your annual salary, medium is a team dinner at a Michelin-starred restaurant, and low is a cup of coffee. High impact puts the company out of business, medium requires major shifts, and low means extra work but nothing crazy.

Step 3: Attack the deal killers. Going around the room, each person lists their “Deal Killers,” the Low Confidence – High Impact assumptions that pose the highest risk to the business. After some discussion to determine the primary assumptions at the beginning of causal chains, you select two for immediate action: (1) Alternative domestic suppliers can be found for the two highest-cost components, and (2) Current manufacturing processes can be quickly adapted to accommodate parts from new suppliers.

A Plan. A Timeline. A Sense of Calm.

With this new narrowed focus, your team sets a shared goal of resolving these two assumptions within 30 days. Together, they set clear weekly deliverables and reallocate time and people to help meet deadlines.

A sense of calm settles on the team. Not because they have everything figured out, but because they know exactly what the most important things to be done are, that those things are doable, and they are working together to do them.

How could you use these three steps to help you move forward through uncertainty?

by Robyn Bolton | Apr 1, 2025 | Leadership, Stories & Examples, Strategy

If you’re leading a legacy business through uncertainty, pay attention. When The Cut asked, “Can Simon & Schuster Become the A24 of Books?” I expected puff-piece PR. What I read was a quiet masterclass in business transformation—delivered in three deceptively casual quotes from Sean Manning, Simon & Schuster’s new CEO. He’s trying to transform a dinosaur into a disruptor and lays out a leadership playbook worth stealing.

Seventy-four percent of corporate transformations fail, according to BCG. So why should we believe this one might be different? Because every now and then, someone in a legacy industry goes beyond memorable soundbites and actually makes moves. Manning’s early actions—and the thinking behind them—hint that this is a transformation worth paying attention to.

“A lot of what the publishing industry does is just speaking to the converted.”

When Manning says this, he’s not just throwing shade—he’s naming a common and systemic failure. While publishing execs bemoan declining readership, they keep targeting the same demographic that’s been buying hardcovers for decades.

Sound familiar?

Every legacy industry does this. It’s easier—and more immediately profitable—to sell to those who already believe. The ROI is better. The risk is lower. And that’s precisely how disruption takes root.

As Clayton Christensen warned in The Innovator’s Dilemma, established players obsess over their best customers and ignore emerging ones—until it’s too late. They fear that reaching the unconverted dilutes focus or stretches resources. But that thinking is wrong. Even in a world of finite resources, you can’t afford to pick one or the other. Transformation, heck, even survival, requires both.

“We’re essentially an entertainment company with books at the center.”

Be still my heart. A CEO who defines his company by the Job(to be Done) it performs in people’s lives? Swoon.

This is another key to avoiding disruption – don’t define yourself by your product or industry. Define yourself by the value you create for customers.

Executives love repeating that “railroads went out of business because they thought their business was railroads.” But ask those same executives what business they’re in, and they’ll immediately box themselves into a list of products or industry classifications or some vague platitude about being in the “people business” that gets conveniently shelved when business gets bumpy.

When you define yourself by the Job you do for your customers, you quickly discover more growth opportunities you could pursue. New channels. New products. New partnerships. You’re out of the box —and ready to grow.

“The worry is that we can’t afford to fail. But if we don’t try to do something, we’re really screwed.”

It’s easy to calculate the cost of trying and failing. You have the literal receipts. It’s nearly impossible to calculate the cost of not trying. That’s why large organizations sit on the sidelines and let startups take the risks.

But there IS a cost to waiting. You see it in the market share lost to new entrants and the skyrocketing valuations of successful startups. The problem? That information comes too late to do anything about it.

Transformation isn’t just about ideas. It’s about choosing action over analysis. Or, as Manning put it, “Let’s try this and see what happens.”

Walking the Talk

Quotable leadership is cute. Transformation leadership is concrete. Manning’s doing more than talking—he’s breaking industry norms.

Less than six months into his tenure as CEO, he announced that Simon & Schuster would no longer require blurbs—those back-of-jacket endorsements that favor the well-connected. He greenlit a web series, Bookstore Blitz, and showed up at tapings. And he’s reframing what publishing can be, not just what it’s always been.

The journey from dinosaur to disruptor is long, messy, and uncertain. But less than a year into the job, Manning is walking in the right direction.

Are you?