How Has Innovation Changed Since the Pandemic? The Answer in 3 Charts

“Everything changed since the pandemic.”

At this point, my husband, a Navy veteran, is very likely to moo (yes, like a cow). It’s a habit he picked up as a submarine officer, something the crew would do whenever someone said something blindingly obvious because “moo” is not just a noise. It’s an acronym – Master Of the Obvious.

But HOW did things change?

From what, to what?

So what?

It can be hard to see the changes when you’re living and working in the midst of them. This is why I found “Benchmarking Innovation Impact, from InnoLead,” a new report from InnoLead and KPMG US, so interesting, insightful, and helpful.

There’s lots of great stuff in the report (and no, this is not a sponsored post though I am a member), so I limited myself to the three charts that answer executives’ most frequently asked innovation questions.

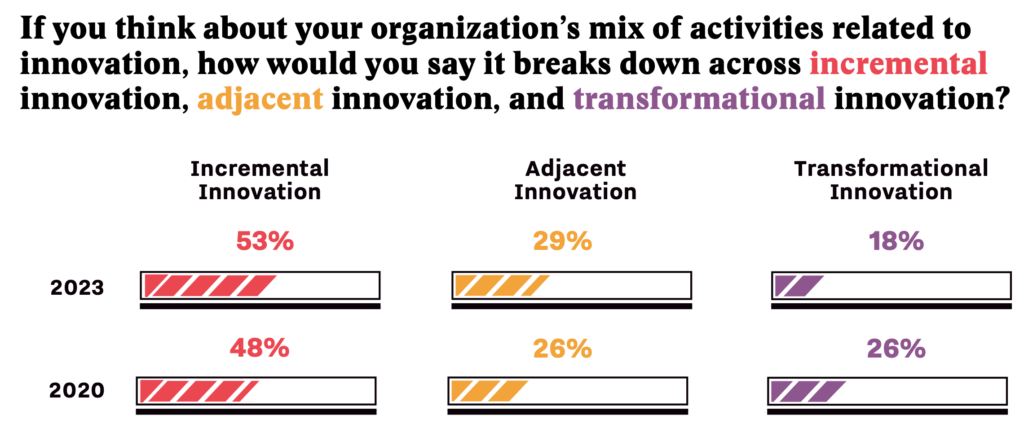

Question #1: What type of innovation should I pursue?

2023 Answer: Companies are investing more than half of their resources in incremental innovation

So What?: I may very well be alone in this opinion, but I think this is great news for several reasons:

- Some innovation is better than none – Companies shifting their innovation spending to safer, shorter-term bets is infinitely better than shutting down all innovation, which is what usually happens during economic uncertainty

- Play to your strengths – Established companies are, on average, better at incremental and adjacent innovation because they have the experience, expertise, resources, and culture required to do those well and other ways (e.g., corporate venture capital, joint ventures) to pursue Transformational innovation.

- Adjacent Innovation is increasing –This is the sweet spot for corporate innovation (I may also be biased because Swiffer is an adjacent innovation) because it stretches the business into new customers, offerings, and/or business models without breaking the company or executives’ identities.

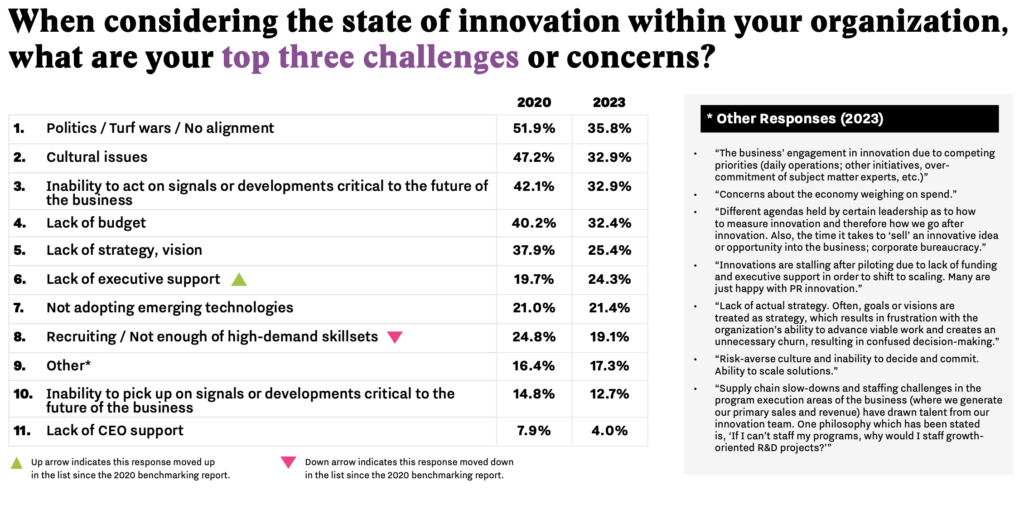

Question #2: Is innovation really a leadership problem (or do you just have issues with authority)?

2023 Answer: Yes (and it depends on the situation). “Lack of Executive Support” is the #6 biggest challenge to innovation, up from #8 in 2020.

So What?: This is a good news/bad news chart.

The good news is that fewer companies are experiencing the top 5 challenges to innovation. Of course, leadership is central to fostering/eliminating turf wars, setting culture, acting on signals, allocating budgets, and setting strategy. Hence, leadership has a role in resolving these issues, too.

The bad news is that MORE innovators are experiencing a lack of executive support (24.3% vs. 19.7% in 2020) and “Other” challenges (17.3% vs. 16.4%), including:

- “Different agendas held by certain leadership as to how to measure innovation and therefore how we go after innovation. Also, the time it takes to ‘sell’ an innovative idea or opportunity into the business; corporate bureaucracy.”

- “Lack of actual strategy. Often, goals or visions are treated as strategy, which results in frustration with the organization’s ability to advance viable work and creates an unnecessary churn, resulting in confused decision-making.”

- “Innovations are stalling after piloting due to lack of funding and executive support in order to shift to scaling. Many are just happy with PR innovation.”

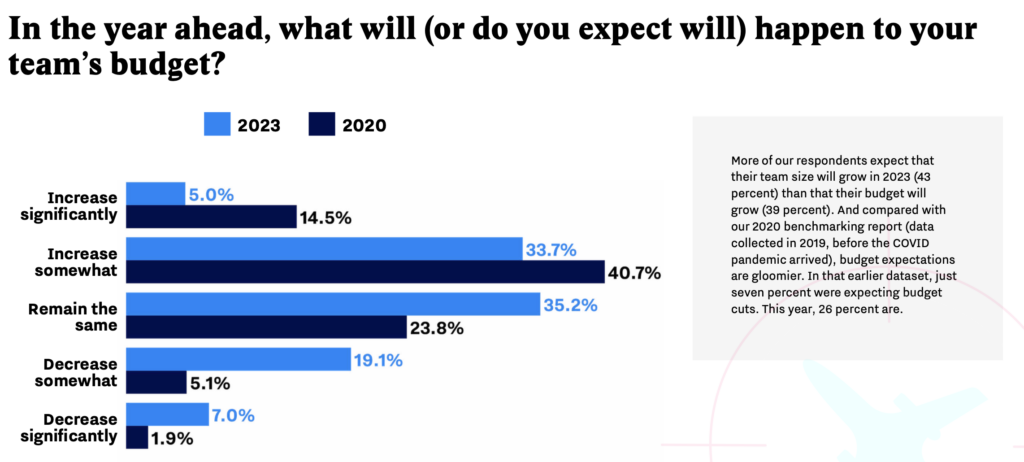

Question #3: How much should I invest in innovation?

2023 Answer: Most companies are maintaining past years’ budgets and team sizes.

So What?: This is another good news/bad news set of charts.

The good news is that investment is staying steady. Companies that cut back or kill innovation investments due to economic uncertainty often find that they are behind competitors when the economy improves. Even worse, it takes longer than expected to catch up because they are starting from scratch regarding talent, strategy, and a pipeline.

The bad news is that investment is staying steady. If you want different results, you need to take different actions. And I don’t know any company that is thrilled with the results of its innovation efforts. Indeed, companies can do different things with existing budgets and teams, but there needs to be flexibility and a willingness to grow the budget and the team as projects progress closer to launch and scale-up.

Not MOO

Yes, everything has changed since the pandemic, but not as much as we think.

Companies are still investing in incremental, adjacent, and transformational innovation. They’re just investing more in incremental innovation.

Innovation is still a leadership problem, but leadership is less of a problem (congrats!)

Investment is still happening, but it’s holding steady rather than increasing.

And that is nothing to “moo” at.