It’s time for your company’s All-Hands meeting. Your CEO stands on stage and announces ambitious innovation goals, talking passionately about the importance of long-term thinking and breakthrough results. Everyone nods enthusiastically, applauds politely, and returns to their desks to focus on hitting this quarter’s numbers. After all, that’s what their bonuses depend on.

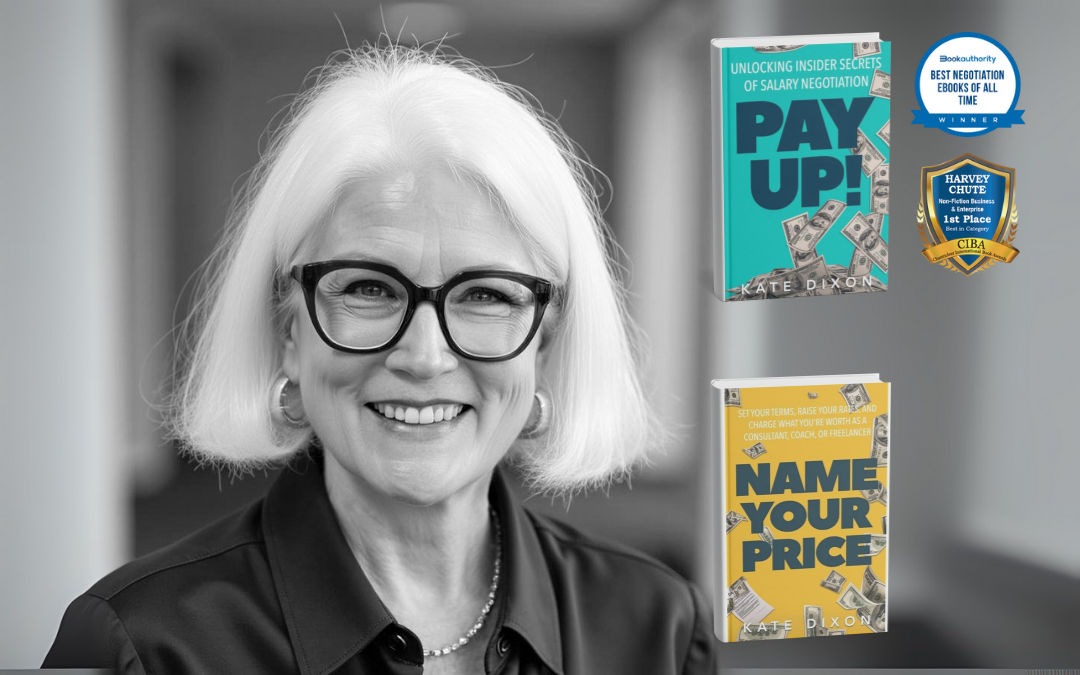

Kate Dixon, compensation expert and founder of Dixon Consulting, has watched this contradiction play out across Fortune 500 companies, B Corps, and startups. Her insight cuts to the heart of why so many innovation initiatives fail: we’re asking people to think long-term while paying them to deliver short-term.

In our conversation, Kate revealed why most companies are inadvertently sabotaging their own innovation efforts through their compensation structures—and what the smartest organizations are doing differently.

Robyn Bolton: Kate, when I first heard you say, “compensation is the expression of a company’s culture,” it blew my mind. What do you mean by that?

Kate Dixon: If you want to understand what an organization values, look at how they pay their people: Who gets paid more? Who gets paid less? Who gets bigger bonuses? Who moves up in the organization and who doesn’t? Who gets long-term incentives?

The answers to these questions, and a million others, express the culture of the organization. How we reward people’s performance, either directly or indirectly, establishes and reinforces cultural norms. Compensation is usually the biggest, if not the biggest, expenses that a company has so they’re very thoughtful and deliberate about how it is used. Which is why it tells you what the company actually does value.

RB: What’s the biggest mistake companies make when trying to incentivize innovation?

KD: Let’s start by what companies are good at when it comes to compensations and incentives. They’re really good about base pay, because that’s the biggest part of pay for most people in an organization. Then they spend the next amount of time and effort trying to figure out the annual bonus structure. After that comes other benefits, like long term incentives, assuming they don’t fall by the wayside.

As you know, innovation can take a long time to payout, so long-term incentives are key to encouraging that kind of investment. Stock options and restricted shares are probably the most common long-term incentives but cash bonuses, phantom stock, and ESOP shares in employee-owned companies are also considered long term incentives.

Large companies are pretty good using some equity as an incentive, but they tie it t long term revenue goals, not innovation. As you often remind us, “innovation is a means to the end, which is growth,” so tying incentives to growth isn’t bad but I believe that we can do better. Tying incentives to the growth goals and how they’re achieved will go a long way towards driving innovation.

RB: I’ve worked in and with big companies and I’ve noticed that while they say, “innovation is everyone’s job,” the people who get long-term incentives are typically senior execs. What gives?

Long-term incentives are definitely underutilized, below the executive level, and maybe below the director level. Assuming that most companies’ innovation efforts aren’t moonshots that take decades to realize, it makes a ton of sense to use long-term incentives throughout the organization and its ecosystem. However, when this idea is proposed, people often pushback because “it’s too complex” for folks lower in the organization, “they wouldn’t understand.” or “they won’t appreciate it”. That stance is both arrogant and untrue. I’ve consistently seen that when you explain long-term incentives to people, they do get it, it does motivate them, and the company does see results.

RB: Are there any examples of organizations that are getting this right?

We’re seeing a lot more innovative and interesting risk-taking behaviors in companies that are not primarily focused on profit.

Our B Corp clients are doing some crazy, cool stuff. We have an employee-owned company that is a consulting firm, but they had an idea for a software product. They launched it and now it’s becoming a bigger and bigger part of their business.

Family-owned or public companies that have a single giganto shareholder are also hotbeds of long-term thinking and, therefore, innovation. They don’t have that same quarter to quarter pressure that drives a relentless focus on what’s happening right now and allows people to focus on the future.

What’s the most important thing leaders need to understand about compensation and innovation?

If you’re serious about innovation, you should be incentivizing people all over the organization. If you want innovation to be a more regular piece of the culture so you get better results, you’ve got to look at long term incentives. Yes, you should reward people for revenue and short-term goals. But you also need to consider what else is a precursor to our innovation. What else is makes the conditions for innovating better for people, and reward that, too.

Kate’s insight reveals the fundamental contradiction at the heart of most companies’ innovation struggles: you can’t build long-term value with short-term thinking, especially when your compensation system rewards only the latter.

What does your company’s approach to compensation say about its culture and values?